Public defense or indigent defense refers broadly to the legal representation afforded to those who cannot afford to retain counsel. The right to publicly funded counsel that we know today if often attributed to the landmark case of Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). In that case, Clarence Earl Gideon was charged with a felony and requested the court appoint him counsel. Although he was indigent, Florida only required that an indigent defendant receive court-appointed counsel in capital cases. Gideon represented himself and was convicted and sentenced to five years. The Supreme Court reversed his conviction, holding that those accused of serious crimes had a fundamental right to counsel and that right was binding on the states based on notions of due process and fairness. Gideon was retried, this time with counsel and was ultimately acquitted of all charges.

Pre-Gideon Right to Counsel

However it is best to understand the right to counsel as a right that has expanded and at times contracted over time. Indeed prior to the landmark Gideon decision, a narrower understanding of the right to counsel for indigent defendants was decided in Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932), also known as the Scottsboro Boys case. Set in the Jim Crown south, the proverbial false rape allegation by two white women lead Alabama officials to charge nine black boys, ages 12-19, with rape. In what can only be described as a series of sham proceedings, the boys were indicted and up until the first day of trial, there had been no attempt to appoint the boys trial counsel and they had not had the opportunity to consult with any such counsel. The unrepresentend accused were tried by all white male juries in trials that lasted only one day. All but the youngest was sentenced to death.

The Supreme Court reversed the convictions stating,

In the light of the facts outlined in the forepart of this opinion -- the ignorance and illiteracy of the defendants, their youth, the circumstances of public hostility, the imprisonment and the close surveillance of the defendants by the military forces, the fact that their friends and families were all in other states and communication with them necessarily difficult, and, above all, that they stood in deadly peril of their lives -- we think the failure of the trial court to give them reasonable time and opportunity to secure counsel was a clear denial of due process.

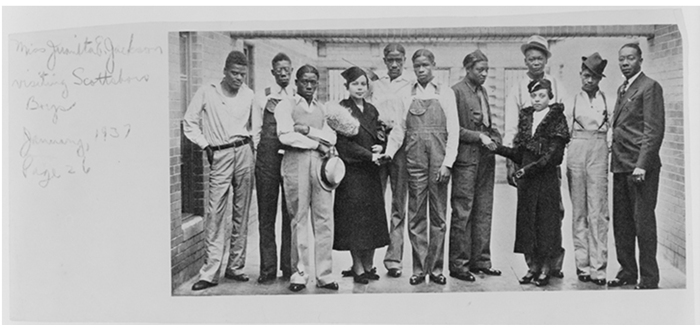

Miss Juanita Jackson visiting the Scottsboro Boys, January 1937. Halftone photomechanical print. NAACP Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (072.00.00) Courtesy of the NAACP

[Digital ID # cph.3c16731].

The Scottsboro case was thus the Court's first attempt at reconizing the need for indigent defense, but only in narrow instances involving capital cases. Six years later, the right to counsel would expand to non-capital cases in Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942), but even that case did not recognize the need for indigent defense in all cases in which a defendant cannot afford counsel. Rather it created a "fundamental fairness" or "special circumstances" doctrine that would govern a case-by-case deployment of counsel for indigent defendants for years to come.

Post-Gideon Right to Counsel

It wouldn't be until 1972 in Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972) when the Court finally ruled:

“that, absent a knowing and intelligent waiver, no person may be imprisoned for any offense, whether classified as petty, misdemeanor, or felony, unless he was represented by counsel at his trial.”

It seemed that the right to counsel would continue to expand and be fortified by the Supreme Court's ongoing jurisprudence, but the 1979 decision of Scott v. Illinois, 440 U.S. 367 (1979) curtailed the right and the Court went on to limit the right to counsel to those instances that involved actual incarceration rather than the threat of incarceration.

The Court had to clarify this holding in Shelton v. Alabma, 535 U.S. 654 (2002) in which a court sentenced a defendant to a suspended term of imprisonment despite the fact that he was not afforded counsel during the trial phase. The Court held that:

a suspended sentence that may "end up in the actual deprivation of a person's liberty" may not be imposed unless the defendant was accorded "the guiding hand of counsel" in the prosecution for the crime charged.

Although the right to counsel has not always expanded, collateral consequences have. Thus the continued need for and strenghtening of the right to counsel remains aspirational. Though Gideon injected hope and revilitalized the public defense discipline, developments in policing and mass incarceration have outpaced the much-needed reforms related to public defense.

For Further Reading

- Irene Oritsweyinmi Joe, Structuring the Public Defender (forthcoming in the Iowa Law Review 2021).

- Joe, Irene Oriseweyinmi, Defend the Public Defenders, The Atlantic, March 13, 2021.

- Public Defenders Suffer From the ‘Stress of Injustice’: Study, Crime Report, January 26, 2021.

- Clair, Matthew, Unequal Before the Law, The Nation, December 14, 2020.

- Frederickson, Caroline, The Unfulfilled Promise of the Public Defender, The Washington Monthly, July 7, 2020.

- Shaun Ossei-Owusu The Sixth Amendment Façade: The Racial Evolution of the Right to Counsel, 167 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1161 (2019).

- Walsh, Dylan, On the Defensive, The Atlantic, June 2, 2016.

- Russell L. Christopher, Penalizing and Chilling an Indigent’s Exercise of the Right to Appointed Counsel for Misdemeanors, 99 Iowa L. Rev. 1893 (2014).

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=1440&height=625&ext=.jpg)