Access to The Champion archive is one of many exclusive member benefits. It’s normally restricted to just NACDL members. However, this content, and others like it, is available to everyone in order to educate the public on why criminal justice reform is a necessity.

The Hanging

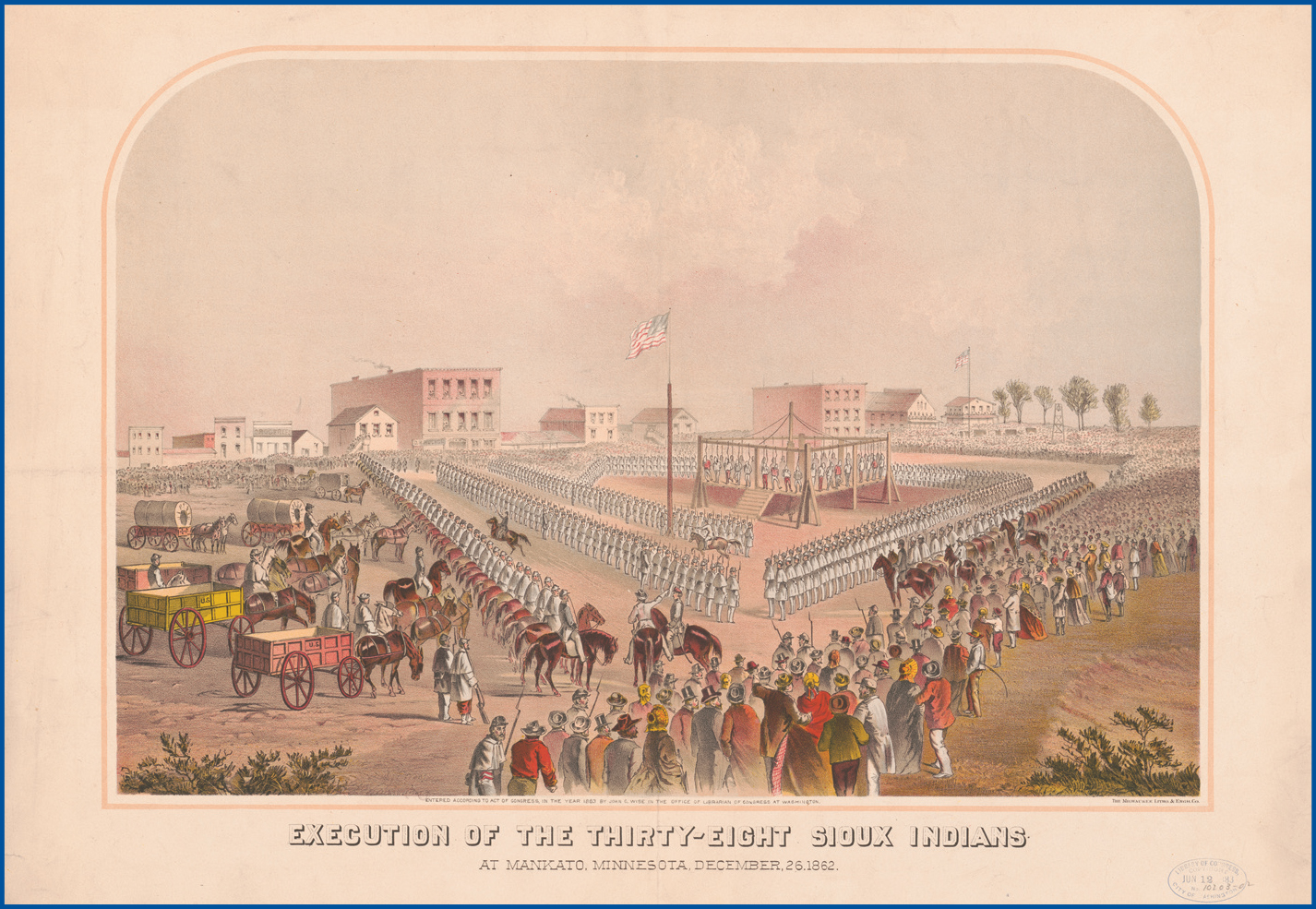

December 26, 1862, was by all accounts a bitterly cold day in Mankato, Minnesota. That particular place on that particular day might not have been noteworthy except that at precisely 10:00 a.m., watched by an estimated 4,000 spectators, the U.S. government hanged 38 Santee Dakota Indians{1} 1 The Dakota referenced in this column refer specifically to the Santee Dakota people of Minnesota. The Santee Dakota people were culturally and linguistically related to, but not the same tribe as, the Lakota peoples of the Oglalla, Teton, Hunkpapa, Yankton, and Brulé bands of the Western Plains. on a scaffold specially constructed for this execution. This became the largest governmental sanctioned execution in the history of the United States. The 38 men and boys were prisoners taken by the United States following the “Dakota Uprising,” which was a five-week conflict between August and September 1862.

The uprising of the Dakota was a predictable result of the long and calculated mistreatment of the Dakota who had originally inhabited a great swath of central and southern Minnesota but by 1862 were confined to a narrow strip of land along the Minnesota river west of Minneapolis. Both the governments of Minnesota and the United States had promised the Dakota that they would receive annuities, including food in exchange for giving up their traditional lands. Quite the opposite occurred, and by 1862 they faced starvation. The uprising was a brutal affair that sent shockwaves through Minnesota and the U.S. government, which was embroiled in the second year of the Civil War. After crushing the uprising, the government incarcerated approximately 2,000 Dakota, including some 1,600 noncombatants.{2} 2 The surviving Dakota people were initially confined at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, located south of Minneapolis. The attitude of the victors was that any Dakota who took up arms was subject to prosecution by the hastily assembled military tribunal.

The Trials

In all the military tribunal would “try” approximately 498 Dakota men and boys. The military tribunal did not conduct the trials at Fort Snelling, where the rest of the Dakota were held, but to the West in Mankato. The trials were adjudicated by officers of the United States Army and Minnesota Militia that had fought against the defendants. The trials commenced on September 28 and would conclude by November 3. On September 28, the tribunal concluded 16 trials. On the last day, the tribunal tried 42 members of the Dakota tribe. By the end, the tribunal tried 393 Dakota and sentenced 303 of them to hang.

Some of these trials lasted no more than five minutes. None of the Dakota, most if not all who had no command of the English language, had interpreters, counsel, or the ability to call witnesses in their defense.{3} 3 Several of the white civilians captured by the Dakota during the uprising had the decency to testify that some of the defendants had cared for and protected them during their captivity.

Racism can be called our nation’s own specific “original sin.”

— Blase J. Cupich{4} 4 In a 2008 editorial, Cardinal Blase J. Cupich said, “Racism can be called our nation’s own specific ‘original sin.’” Blase J. Cupich, Racism and the Election, America: The Jesuit Review (Oct. 27, 2008), https://www.americamagazine.org/issue/673/editorial/racism-and-election.

President Lincoln asked for a “full and complete record” of the convictions following the trials. Lincoln would ultimately commute the death sentences of all but 38 of the defendants. He would explain his reasoning in a message to the United States Senate: “Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be seen as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records to be made.”{5} 5 Message to the Senate Responding to the Resolution Regarding Indian Barbarities in the State of Minnesota. Abraham Lincoln (Dec. 11, 1862).

Lincoln’s review was probably of little comfort to the family of a young Dakota named Chaska. Despite his sentence being commuted by Lincoln, Chaska was hanged along with the others on December 26.{6} 6 Chaska’s full name was We-Chank-Wash-Ta-don-pee, which means Good Little Stars. It is ironic that Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation five days after the 38 were hanged.{7} 7 The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by Executive Order on Jan. 1, 1883.

Extraordinary Rendition

The mass hanging of December 26 was not the end of the dubious application of legal principles and proceedings against the Dakota. In January 1864, three Dakota tribal leaders who had fled Minnesota to Canada were kidnapped, drugged, and smuggled back across the border to Minnesota, where the government hanged them a year later. Congress later passed legislation making it illegal for Dakota to live in Minnesota.

Whose Law Applies?

Our criminal legal system was not finished with the Dakota and Lakota peoples. Despite a concerted and government-sanctioned attempt to forcibly destroy native culture, the tribal societies hung on.{8} 8 In 1892, Richard Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian School, would famously state: “All the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” The tribal way of resolving criminal acts was and is radically different than the Anglo-American criminal legal system. Tribal councils traditionally focused on restitution to the harmed, not only as an atonement for the act but as a form of community healing. The concept of execution or imprisonment was practically unknown in traditional tribal societies. Even after the establishment of reservations, tribes with which the United States had treaties were considered sovereign nations. As such, our courts recognized that it was legally permissible to try and punish Native Americans for crimes committed on state or territorial land, but deference was given to the tribes to punish crimes committed by Natives against other Natives on tribal lands. Of course, any alleged crimes or threat of crimes committed by Natives against non-Natives on tribal lands would invite the intervention of the United States Army, with tragic results.{9} 9 The Massacre of the Lakota at Wounded Knee occurred within the bounds of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Drawn by W. H. Childs in 1862, this work illustrates the largest mass hanging in American history, when 38 Sioux Indians were executed, presumably for deeds committed during the Dakota Wars. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-07671

This status of quasi sovereignty had been established as early as 1832 in Worcester v. Georgia{10} 10 Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515, 6 Pet. 515, 8 L. Ed. 483 (1832). when Justice Marshall, writing for the Supreme Court, reasoned that the United States inherited the same rights and obligations, by way of treaties with the tribes, that had belonged to the Crown of Great Britain. Marshall reasoned that since, at the time of independence, the King could only cede to the United States what had belonged to the Crown and the Crown had held the tribes with which it had treaties to be sovereign nations, so must the United States. Although this was a victory for the petitioner, Samuel Worcester, a non-Native whom the state of Georgia indicted for “residing within the limits of the Cherokee Nation without a license,{11} 11 Samuel Worcester was a missionary to the Cherokee Indians and a vocal defender of Cherokee Sovereignty. He was a thorn in the side of the state of Georgia, which sought to open up Cherokee lands to mining interests. the opinion would be of no help to the Cherokee who would be forcibly removed from Georgia to Oklahoma by President Andrew Jackson five years later.{12} 12 Andrew Jackson would famously state, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”

Crow Dog and the Major Crimes Act

In 1883 a seismic shift would take place in the legal status of Native Americans in the criminal legal system. This would arise from the prosecution of a Brulé Lakota chief named Crow Dog. Crow Dog shot and killed another Brulé Chief named Spotted Tail. The killing took place within the bounds of the Brulé lands on the Rosebud Indian Reservation.{13} 13 The Rosebud Reservation is located in South Dakota on land that once encompassed the “Great Sioux Reservation.” Much of this territory was lost to the Lakota as a result of the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, which broke up into smaller reservations what had once been a contiguous expanse of land encompassing the Western half of South Dakota, Western Nebraska, Eastern Wyoming, as well as portions of Montana and North Dakota. The killing of Spotted Tail was brought before the tribe and resolved according to the traditional Lakota customs.{14} 14 The restitution consisted of up to 600 dollars, eight horses, and a blanket. This resolution did not satisfy the white Indian Agent, Henry Lelar. It is possible that Lelar was biased against Crow Dog because Spotted Tail had allegedly been willing to sell Lakota lands to white ranchers, a policy that Crow Dog adamantly opposed. Lelar had Crow Dog arrested. He was subsequently indicted by a Federal Grand Jury and brought to trial in the Federal Court for the Dakota Territory.{15} 15 South Dakota would not become a State until 1889. The trial would be held in Deadwood, South Dakota.{16} 16 Deadwood had been illegally established in the 1870s by gold miners, in violation of a treaty between the United States and the Lakota. It was an ironic choice of venues given the ethnicity of the defendant. The defense was that Crow Dog had acted in self-defense and, even if he had not, the matter had been resolved according to tribal custom. Despite the holding of Worcester, the Territorial Court rejected the jurisdictional argument and, upon Crow Dog’s conviction for murder, sentenced him to hang on May 11, 1882. The judge, perhaps recognizing his elastic interpretation of federal jurisdiction might be challenged, allowed Crow Dog to return home pending his appeal with the understanding that Crow Dog would appear for his hanging at the appointed time.

To the surprise of the non-Native people of the Dakota Territory, Crow Dog, true to his word, appeared on time for his surrender but, fortunately for him, a habeas petition was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court unanimously decided that the Dakota Territorial Court lacked jurisdiction. The Court focused upon the fact that the offense had occurred within “Indian Country” and that within such Congress had expressly excepted “crimes committed by one Indian against the person or property of another Indian.”{17} 17 Ex Parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556, 562, 3 S. Ct. 396, 27 L. Ed. 1030 (1883). As a result of this decision, Congress would enact the Major Crimes Act,{18} 18 See 18 U.S.C. § 1153. which placed certain enumerated crimes under federal jurisdiction if committed by an “Indian” against another “Indian.” Three years later, this would be expanded to crimes committed on an Indian reservation as a result of the Supreme Court’s holding in United States v. Kagama.{19} 19 United States v. Kagama, alias Pactah Billy, an Indian, and Another, 118 U.S. 375, 6 S. Ct. 1109, 30 L. Ed. 228 (1886).

McGirt

Despite the enactment of the Major Crimes Act and its expansion care of the Kagama decision, there has been some relief for Native Americans facing state prosecution. In 2020, Justice Gorsuch authored the opinion in McGirt v. Oklahoma.{20} 20 McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. 894, 180 S. Ct. 2452, 207 L. Ed. 2d 985 (2020). The McGirt opinion defined, for jurisdictional purposes, what constitutes “Indian Country” and established that criminal jurisdiction for acts allegedly committed by Native Americans on tribal lands, established by treaty with the United States, falls exclusively within the jurisdiction of the tribal courts, or the Federal Courts if such act is enumerated under the Major Crimes Act.{21} 21 Although McGirt specifically references the “Five Civilized Tribes” of Oklahoma, it may implicate other tribes in Oklahoma and elsewhere. The “Five Civilized Tribes” is a term used to describe the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole peoples driven from their lands in the Southeastern United States to Oklahoma by Andrew Jackson. The fallout from McGirt has been significant, especially in Oklahoma. Primarily, a massive burden has fallen upon the Federal Defenders of the Eastern District of Oklahoma because the majority of the tribal lands covered by McGirt are within this district. Soon after the Supreme Court decided McGirt, NACDL consulted with the Federal Defenders and began a collaborative effort to offer trainings to State practitioners whose clients might chose to have their cases transferred to Federal Court. Many NACDL members have volunteered to take on clients facing trials, resentencings, and sentencings within the Eastern District.

Going Forward

NACDL has begun an outreach to tribal defenders, tribal courts, Native American law students, and nonindigenous defenders who represent people in the criminal legal system to begin the process of ensuring that to the extent the criminal legal system works for anyone, it works for those who are the multigenerational victims of our nation’s original sin. It is anticipated that NACDL will continue to advocate for a meaningful defense function for all Native Americans facing criminal charges, whether in tribal courts, state courts, or federal courts. This is not an easy task. The abysmal lack of resources allocated to tribal courts and tribal lands is a shameful blot on the proverbial escutcheon of our nation. However, this is not an excuse to act. Quite the contrary. Millions of our fellow Americans need us and the ghosts of 38 Dakota are watching us.

About the Author

Christopher A. Wellborn is a founding member and past president of the South Carolina Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. He practices in state and federal courts, representing clients facing all types of misdemeanor and felony charges, including drug charges, traffic offenses, white collar crimes, and juvenile offenses. Wellborn is sought after nationwide for his experience with unwarranted charges of shaken baby syndrome and child abuse.

Christopher A. Wellborn (NACDL Life Member)

Christopher Wellborn PA

Rock Hill, South Carolina

803-366-1065

cawlaw@comporium.net

www.wellbornlawfirm.com