Access to The Champion archive is one of many exclusive member benefits. It’s normally restricted to just NACDL members. However, this content, and others like it, is available to everyone in order to educate the public on why criminal justice reform is a necessity.

Professors and students at South Texas College of Law Houston (STCL) were instrumental in convincing the U.S. Army to overturn the 100-year-old convictions of 110 Black soldiers that stemmed from the Camp Logan riots, including 19 who were executed.

In August 1917, members of the 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, an all-Black Army unit, left their barracks in Houston to challenge what they believed to be a white mob that meant to harm them. A riot ensued; several soldiers and local people died. The 110 Black soldiers were court-martialed, and their murder trial contained “numerous irregularities,” according to an Army press release. The Army lynched 19 of the soldiers, with some of the lynchings occurring “in secrecy and within a day of sentencing.”

Ashley Cromika, a Houston attorney, researched the cases when she was a student at STCL Houston. Professor Catherine Greene Burnett, vice president and associate dean for experiential learning, oversees the actual innocence clinic and supervised some of the student researchers. I spoke with Cromika and Burnett about the Camp Logan soldiers’ 100-year journey from conviction to justice.

Michael Heiskell (MH): The U.S. Army overturned the convictions of 110 Black soldiers in November 2023. The men were part of the all-Black unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers. This is an effort obviously by the Army to atone for harsh punishments linked to the Jim Crow-era racism that was ongoing in this country at that time. How did this case come to the attention of South Texas College of Law Houston?

Professor Catherine Greene Burnett (CB): It takes a village to do anything worthwhile in life. This is a story that illustrates how many people are involved. You have two of us in this interview, but there could be another 20 behind me. Librarians at the law school were approached to digitize the records from these courts-martial. When a retired JAG officer joined our faculty — Professor Geoffrey Corn — one of the librarians mentioned to him, “We’ve got these records, and it was really a thing.” He hadn’t heard of it, just like almost no one in America seems to have heard about it very much. He started reading the records and involved retired JAG officer Professor Dru Brenner-Beck. She actually filed the petition. The NAACP got involved. Geoffrey Corn got me involved. I got Ashley involved. It was a multiyear process.

MH: Tell us how this began in 1917.

CB: It really is an illustration of miscommunication and the impact that it can have. There was a horrible incident in which two white Houston police officers approached and harassed an African American woman living near the camps. I think they suspected there was gambling or something else going on. They ended up chasing her into the street in her night clothes. Corporal Baltimore, who was a military police officer at the time, witnesses this and asked the police what they were doing, why were they approaching this woman in this way, and what was going on — that sort of good police work that we would expect to see from an MP. The Houston police officers responded by attacking, pistol whipping, and shooting at him. Soldiers in the 24th Battalion began to believe that the Houston police killed Corporal Baltimore. That was the miscommunication. Officers from the camp went to the police department and confirmed that Corporal Baltimore was alive, but by then the rumor mill had started on both sides. The soldiers of the 24th, I think, became convinced that a white vigilante mob was coming to Camp Logan to attack them.

Ashley Cromika (AC): There was definitely a lack of communication. They didn’t let the soldiers know — even hours after the officers knew that he was OK. There was unrest in the camp. People were not in a great state of mind. They didn’t do anything to try to mitigate that. As a matter of fact, I think a couple of the officers, even knowing that this was going on and that there was talk of vigilante justice from the Houstonians, I think they still took passes and actually went outside of camp. So, they didn’t even have the appropriate number of officers in charge when all of this occurred.

MH: What kind of research did it take to convince the U.S. Army that a wrong had taken place 100 years ago that needed to be corrected? You mentioned the digitizing that started this project. Did you have to examine sources other than those digitized records?

|

|

| Professor Catherine Greene Burnett | Ashley Cromika |

CB: Absolutely. We digitized some letters from soldiers and the courts-martial, but Ashley went above and beyond that to give a context and a life and a history to the soldiers who were impacted.

AC: I started at the National Archives online. We were in the middle of COVID, so there weren’t any places to go put your hands on documents. Everything was shut down. The National Archives had several people doing satellite work, and for five months I searched for anything about that unit, about Houston, and about Camp Logan in general. When I found something that wasn’t digitized in the National Archives, I wrote down the document number and requested that someone scan it and send me a copy.

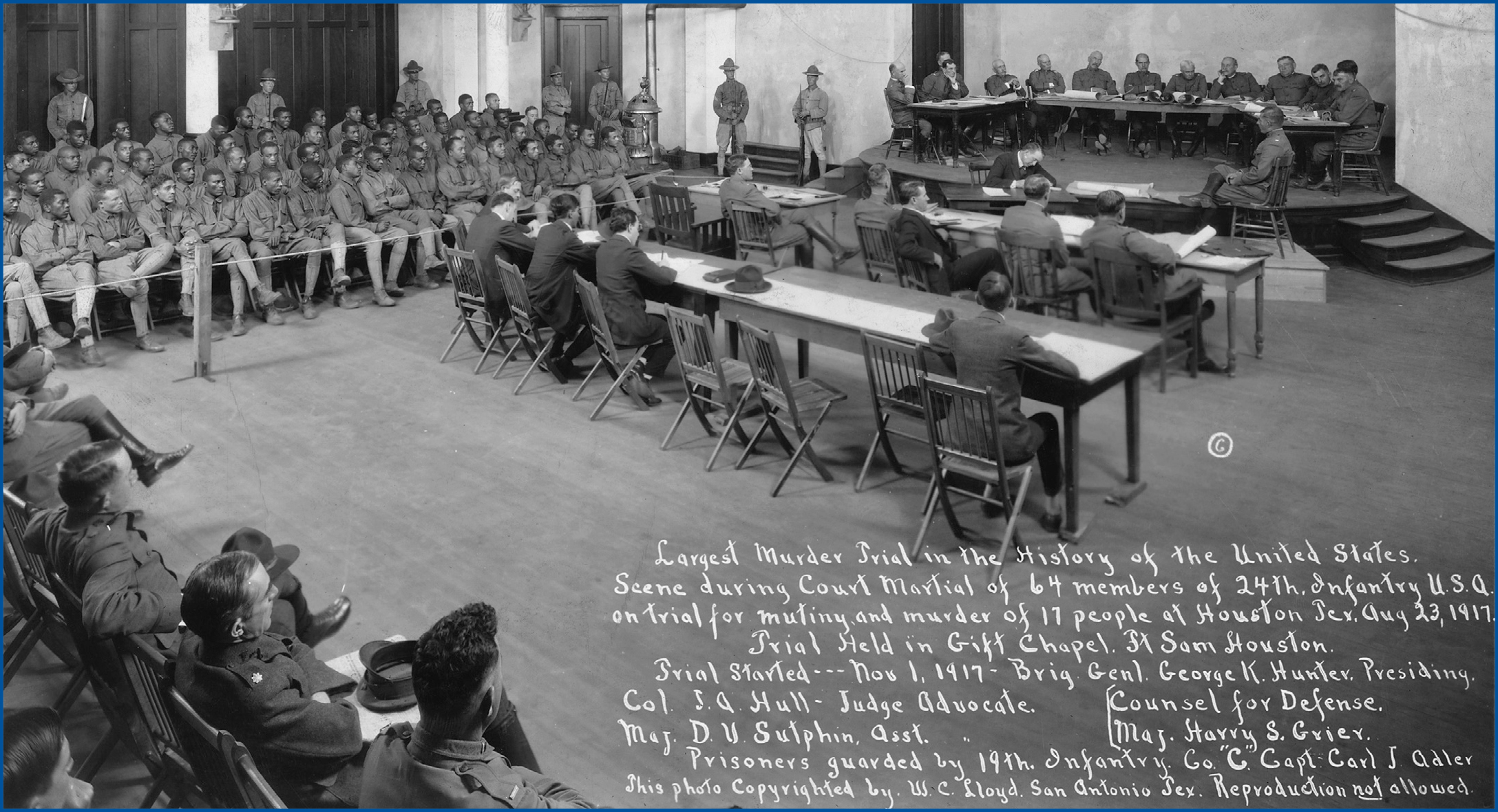

MH: It is powerful to see the courtroom photo. You uncovered letters some of these soldiers had written to their families. They knew that their fate was at hand. Describe the impact those letters had on you and the rest of the team.

AC: The photo has such a great impact. It is emotional, draws you in, and makes you want to work harder to find more. I think the men had already been executed by the time the families received those letters. Their families didn’t even know that it had happened yet. I found pictures of the soldiers, including pictures of them when they went through processing at Fort Leavenworth. I also found medical records and all the communications between everybody at JAG back and forth about this. It humanizes everything. Reading the letters, reading the communications, and seeing the medical records makes you want to work harder and fight harder.

MH: “If you care, you prepare,” is my mantra. You have to care about something or someone in a particular case in order to engage in thorough preparation. I’m sure that seeing those materials that humanize things — the letters and medical records — was an impetus for you to keep going.

CB: Some of the soldiers were children. They would have been in high school in today’s world. Other members of this group were seasoned veterans who had fought honorably in campaigns in the Spanish-American War and in General Pershing’s raids into Northern Mexico from Texas in pursuit of Pancho Villa. These were heroes. They weren’t a mob. That’s one of the things that bothers me when I read the record. I think it was their belief that there was a vigilante mob coming for them. They responded in a military way. They were in formation. They weren’t just running all over the place. They were responding like the professional soldiers that they were, thinking they were being attacked.

MH: What were the problems with those proceedings in 1917?

CB: They were all legal, right? It reminds me of the infamous case from about that same period of time sometimes referred to as the Scottsboro Boys. It was lawful, but nobody could say it was “just.” It’s a lot like Powell v. Alabama. We can’t say that due process occurred here. There were dozens of people in a trial with one representative who wasn’t a lawyer?

AC: Yes. The first 63 people and one representative.

CB: Sixty-three people and one representative, a nonlawyer, with little time to prepare. He had incentivized witnesses. Today we look with skepticism at incentivized witness. This case involved cross-racial ID of young men in the rain, in uniforms, with almost the same haircut. How could you even distinguish? We have records that say one person was there, another hearing that says, “Oh, this person wasn’t there.”

AC: Several people had the same last name. They all went by their last name, so it wasn’t like there’s John Smith and there’s Joe Smith and there’s Bob Smith. It’s just, “I saw Smith here.”

MH: Were you able to determine whether defense counsel had sufficient time to prepare an adequate defense?

AC: I don’t think there was an adequate time to prepare even a “less than ideal” defense.

MH: In that photograph, all these men in their uniforms are sitting on one side in that courtroom. How could you even try people that way? That, in and of itself, seemed to be an insurmountable problem from the defense standpoint — to be able to defend themselves individually as well as collectively from these heinous charges.

CB: What about conflict of interest? If I were representing one of the younger soldiers — for example, a 17-year-old whom I believe was following orders that he got from a more senior sergeant in his unit — then that would have been my defense. But if I’m also representing the sergeant, how can I raise that issue? It is shocking. And the racial tension did not get very much attention.

MH: Have you talked to the family members of the soldiers?

CB: Camp Logan is on the grounds of what is now Memorial Park in Houston. The Memorial Park Conservancy has done a tremendous job trying to honor the soldiers and make Houstonians aware of that event. The Conservancy has had a series of dinners and meetings that have brought together descendants. We speak to them frequently, probably about every five months. The niece of one of the executed soldiers is a professor at Prairie View A&M. I talk to her frequently.

Aug. 23, 1917 — Court Martial of 64 members of the 24th Infantry on trial for mutiny and murder of 17 people in Houston, Texas. Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 165-WW-127(1)

MH: What did your work on this project teach you about justice?

AC: Justice is obviously important, and we want it to be timely. We want things to be done right, but so many problems exist. We see progress, but we must acknowledge that things were done incorrectly. Seeking justice for the Camp Logan soldiers — even if 100 years later — is part of making that progress. Some people said, “I don’t know why anybody is taking the time to do this or worry about this. That was 100 years ago. Focus on stuff that’s happening today.” We can’t focus on stuff today if we don’t fix what we broke in the past. It’s just going to repeat itself if we don’t. We have to acknowledge it and fix it so that we can move forward in a positive way.

CB: I’m proud of the Army. The Army didn’t sweep this under the rug. It didn’t pretend that this didn’t happen. The Army didn’t say, “We complied with all the procedures that were in place at the time. This was done exactly according to the letter of the law.” Instead, the Army stepped up.

MH: What do you think the students in the innocence clinic learned about wrongful convictions after working on this case?

CB: Maybe they learned it is never too late to acknowledge what was done and how things can be better in the future.

MH: Did working on this project influence any students to become criminal defense attorneys?

CB: Sadly, no. It may have had the opposite impact. In the clinic, we look at all the root causes of wrongful conviction, and many of them were present here. I think that inadvertently, perhaps, some of the messaging is that things have not radically changed in 100 years. Systemic racism is still a critical part of the criminal justice system. Identifications are still an issue. Incentivized witnesses are still an issue. Exculpatory evidence is still an issue. The positive side is that I have Ashley, who is a civil lawyer, and she cares. So, now we have this army of people who are on the civil side who will raise the conversation. It’s not just the usual suspects like you and me, Mike, and a bunch of criminal defense lawyers. We have our civil law sisters and brothers caring about it too, and that is a positive development.

MH: The Camp Logan case also provides a lesson on the importance of having a zealous advocate to represent each defendant.

CB: It must have been shocking for my students to read the record and see the utter disconnect between what we know of as a trial in 2024, even with today’s flaws, and the Camp Logan proceedings in 1917. Those proceedings did not bear much resemblance to what we have today.

AC: We were reading the transcript to identify red flags, which appeared on page after page. One has to appreciate the fact that we have progressed so much as a society just in our criminal justice system.

MH: I am thrilled to talk to two people who have rewritten history. Congratulations to you for playing a role in getting these soldiers’ military service records corrected to show that they served their country honorably. It is keenly important to our system of justice and to the families of these men to have corrected their legacy.

Questions and answers have been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Read more about the Army proceedings.

About the Author

Michael P. Heiskell is the owner of Johnson, Vaughn & Heiskell in the Fort Worth-Dallas, Texas area. He represents individuals and entities in state and federal courts throughout the country, with an emphasis on white collar investigations and prosecutions. He is a past president of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyer’s Association.

Michael P. Heiskell (NACDL Life Member)

Johnson, Vaughn & Heiskell

Fort Worth, Texas

817-457-2999

mheiskell@johnson-vaughn-heiskell.com

www.johnson-vaughn-heiskell.com