Access to The Champion archive is one of many exclusive member benefits. It’s normally restricted to just NACDL members. However, this content, and others like it, is available to everyone in order to educate the public on why criminal justice reform is a necessity.

Seldom do the policies of prosecutors’ offices come to light. As defense lawyers in state courts, we hear over counsel table what plea offer is being extended, but seldom is the reasoning behind the plea offer explained. There is claimed discretion by line prosecutors, but we know there is an entire structure of internal controls in place designed to eliminate prosecutorial discretion. Case resolution statistics are documented, approved by supervisors, and in most states, the numbers are reported to state agencies for political purposes and to justify future budget requests.

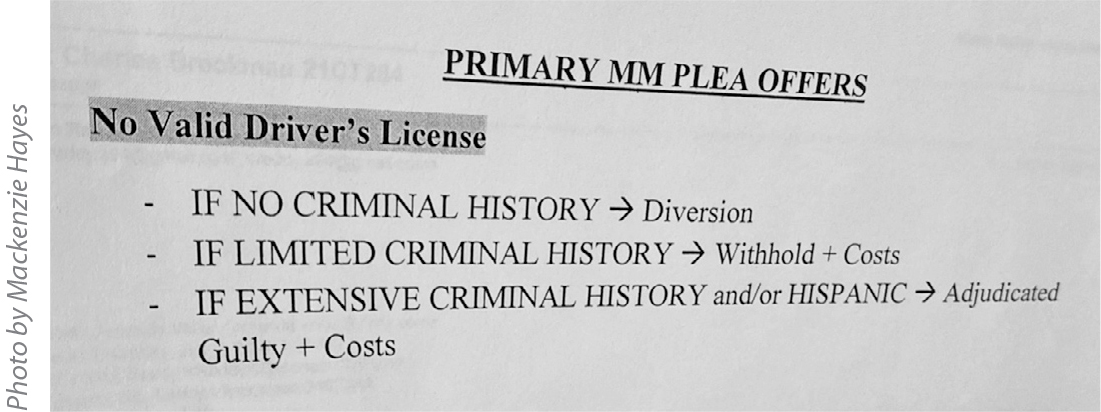

When an overtly racist, and seemingly illegal, written policy to punish Hispanic defendants more harshly than non-Hispanic defendants in Jefferson County, Florida, was outed in April, the race-based motivations for plea offers extended in that circuit made international news. In addition to clamoring for state and federal investigations into these practices, it prompted an important national discussion on these issues.

Whistleblowing Assistant State Attorney Mackenzie Hayes uncovered the policy. She came across an internal document directing prosecutors to offer more stringent plea deals in driver’s license cases to defendants with “extensive criminal history[ies]” or if the individuals are “and/or HISPANIC.” Those judged to be of Hispanic descent would be adjudicated guilty, whereas a diversion plea offer or a no-conviction disposition was recommended to “non-HISPANIC” defendants. Hayes quit after working at the satellite office for five days, noting in media pieces there was a “glaring difference in the state attorney’s office culture and views on race.” She now works for Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s progressive district attorney.

Jefferson County is where elected State Attorney Jack Campbell oversees a satellite office of prosecutors from his main office in Tallahassee, 25 miles away. With approximately 14,500 people, Leon is the third most rural county in Florida, agriculture serves as the economic base (24% of the county income is derived from agriculture and forestry), and migrant farm labor is critical to work the land. Given the environment, the impact of this race-based policy is significant and the harm substantial. Disparate treatment of this population is not isolated to one county, or just to Florida, however. Most defenders simply do not have written proof of the racism their clients encounter in courtrooms across this country.

When confronted with his office’s policy, Jack Campbell first blamed the subordinate, condemning the choice of words and indicating the memo should have read “undocumented immigrants.” This outward expression of equating a Hispanic person with an immigrant served to dig the hole deeper for Campbell, demonstrating a complete lack of understanding around race, ethnicity, and immigration status, and with powerful implications for those defendants on the receiving end of this racist approach to minor traffic offenses. The conviction mandate for Hispanic defendants means deportation for some, as well as other serious collateral consequences that accompany a conviction. The disparate treatment aspect of this policy implicates civil rights violations because of the racial profiling of Hispanic people. The protocols also appear to violate 18 U.S.C. § 242, which prohibits treating non-citizens more harshly than U.S. citizens. It is also deeply offensive from a moral standpoint.

Campbell’s claimed justification for the policy has changed, however, as pressure has mounted from his counterpart, Jessica Yeary, the elected Public Defender in Florida’s Second Circuit, as well as the Southern Poverty Law Center and the ACLU. In addition to far-reaching investigations into the plea practices there, the groups are calling for cases to be assessed based on the equal protection impact of Campbell’s plea bargaining practices and are demanding that matters be brought back before the courts for reconsideration.

Notably, Yeary’s tenure as the Public Defender has been dedicated to fighting racist systemic issues in Tallahassee and the surrounding counties long before this memo was leaked. In my estimation, “Campbell-gate” represents just the tip of the iceberg as far as what will be uncovered in that jurisdiction pertaining to how Brown and Black people are treated in the criminal legal system. I applaud these efforts and hope it leads to change in Florida, a state where one in four people are Latinx.

This internal policy outing highlights the fact that racism and discrimination stand as foundations in our criminal legal system. As we know, these practices most commonly operate insidiously inside courtrooms every day across this country, but out of view in a way that can be legally challenged. Here, the racist tactics were brazenly posted to the walls of a government building. When record evidence emerges of racially motivated plea offer decisions, it serves as motivation for all of us to examine the policies, procedures, and data in our local jurisdictions around how people of color are treated by the prosecution, law enforcement, and the courts.

About the Author

Nellie L. King is the owner of the Law Offices of Nellie L. King, P.A. She practices criminal defense in state and federal courts throughout the United States and lectures on criminal legal reform and constitutional issues. She is a Past President of the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

Nellie L. King (NACDL Life Member)

Law Offices of Nellie L. King, P.A.

West Palm Beach, Florida

561-833-1084

Nellie@CriminalDefenseFla.com

www.criminaldefensefla.com