Every time a police officer puts his left hand on the Bible, raises his right hand in the air, and swears to tell the truth and nothing but the truth, he is inviting the factfinder to judge his credibility. For defense attorneys operating in a world in which “blue lives” matter and police officers are revered as inherently trustworthy, this creates an uphill battle. That hill is steeper when it comes to motions to suppress evidence seized in searches with or without a warrant because it is the judge alone who decides whether the officer is telling the truth.

Every time a police officer puts his left hand on the Bible, raises his right hand in the air, and swears to tell the truth and nothing but the truth, he is inviting the factfinder to judge his credibility. For defense attorneys operating in a world in which “blue lives” matter and police officers are revered as inherently trustworthy, this creates an uphill battle. That hill is steeper when it comes to motions to suppress evidence seized in searches with or without a warrant because it is the judge alone who decides whether the officer is telling the truth.

The law will not save the day. Defense attorneys like to think that standards such as “probable cause” and “reasonable suspicion” are stalwart legal principles with clear definitions, but the case law tells a different story. These standards have been described by State and Federal courts as “flexible,” “fluid,” and “case dependent.”1

Current events will not save the day. Despite the constant flow of news stories about police corruption, no judge wants to call an individual police officer a liar.

The defense case will not save the day. Judges look at cases through their lenses rather than through the lens of the accused. This extends to the court’s view of defense witnesses; it is rare that calling a witness to directly contradict a police officer proves a winning strategy.

When all is said and done, criminal motion practice boils down to the credibility of the officer making the assertion and to the ability of criminal defense attorneys to strip away the presumption of trustworthiness that comes with a badge and a gun. And so, like Sisyphus, every time defense attorneys file a motion to suppress they start pushing an enormous boulder up that steep hill.

To break the cycle, defense lawyers must embrace the reality that theirs is not a problem of law. It is a problem of fact. This is not to suggest that advocates should not vigorously pursue Fourth Amendment challenges. For trial lawyers, however, after a ruling comes down they are stuck with it until an appellate court reverses it. This concept is cold comfort to the client. What trial lawyers can do in the moment for their clients is to make better credibility arguments that may succeed even when the law, the system, and the factfinder’s worldview are against them.

Defense lawyers argue credibility differently by doing the following:

1. Making it impossible (or at least difficult) for the court to ignore that the officer’s inconsistencies actually mean something.

2. Exploring police officer bias more fully and meaningfully.

3. Observing, recording, and commenting on demeanor.

4. Applying systemic arguments to individuals, particularly when it comes to implicit racial bias.

5. Arguing noncompliance with established police procedures.

6. Making it personal by telling the story of the client’s experience.

7. Combining visual aids with storytelling.

Making It Impossible

Lawyers make most credibility arguments on the fly after the hearing has concluded. The arguments sound something like this:

- “But your honor, the officer was inconsistent.”

- “The officer did not seem to be telling the truth.”

- “His testimony did not have the ring of truth.”

What do these arguments mean? Nothing. When defense lawyers believe that the officer is lying through his teeth and assume that everyone else can see it, they make a critical mistake. It is the mistake of expecting the court to see things through the lawyers’ lens when they have offered no reason to do so. The result is that the defense loses control of the analysis, does not give the judge a coherent framework in which to assess credibility, and winds up allowing judges to fall back on their worldview and preconceived ideas. The boulder rolls right back down the hill.

My mother always told me, “The truth is the same no matter how many times you tell it.” This means that when a person is telling the truth, the story should not change in material ways from telling to telling. One of the instructions many states give juries is that they may and should consider inconsistencies in the testimony of witnesses when evaluating their credibility. Even in daily life, people disbelieve a person when his story changes over time.

Inconsistent statements are the greatest weapons in the defense team’s credibility arsenal. Rather than talking about them generally and arguing the officer was “inconsistent,” the defense must highlight the inconsistencies in ways the court cannot explain away or ignore.

Impeachment is only the beginning. After defense lawyers have impeached, they should think through how to present the inconsistencies as part of a coherent argument about credibility. Gathering inconsistent statements is one way to achieve this result. Attorneys too often discuss inconsistencies as they pertain to a discrete portion of their argument. For example, assume that an officer was inconsistent about the color of the car and the time the accused signed a consent to search form, and that both issues are material to the outcome of the motion. Many attorneys will discuss the inconsistency about the color of the car when they discuss the stop, and wait until they discuss consent to highlight the difference in testimony about the consent form. Presenting inconsistencies in isolation gives the factfinder the opportunity to dismiss each as inconsequential. A better way would be to group the two statements for maximum effect in a separate section of the argument about officer credibility. This is not to say that counsel cannot address these items a second time in the appropriate section of the argument, but making a separate and specific argument about credibility on its own as opposed to joined together with other arguments goes a long way to convince the judge that a particular inconsistent statement is not an accident or oversight.

Discussing inconsistencies collectively also allows defense counsel to include minor discrepancies along with the more material ones. Using the same example, assume that the officer was also inconsistent about the hand in which the accused carried an item and the color of his jacket, but that these are not necessarily critical to the motion’s outcome. Many attorneys skip over the minor issues because they assume the judge will ignore them, or they refuse to argue the minor issues because they are not outcome-determinative. However, there is a place for these facts. Including the minor inconsistencies in the credibility section of the argument gives more weight to the argument that the material inconsistencies were deliberate. Even small inconsistencies or omissions become important when presented in bulk.

Consider the order in which inconsistent statements are addressed. Start from the most material impeachments and end with the least. Demonstrating to the court that the officer testified differently about material facts may cause her to pay more attention to the minor inconsistencies. Beginning with the strongest impeachments also makes it more difficult for the judge to dismiss the less significant ones.

Do not forget to include omissions in reports. When reviewing the police report for cross-examination, the defense attorney should ask herself, “What would the perfect officer have included in this report to support these claims?” This should be a regular part of any pre-motion brainstorm. Anything that is not in the report but should be is fair game as an omission. Like minor inconsistencies, omissions can buttress an argument that a witness’s changed testimony is willful rather than just an innocent mistake.

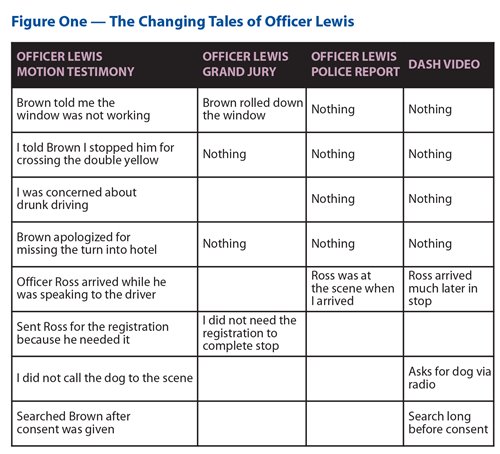

Imagine ways to present inconsistent statements or omissions visually. Make a chart of what has been developed through the motion. Rather than arguing, “The officer testified inconsistently with his police report” and then reading the inconsistencies in a list, show the chart to the judge so he can not only see the nature but also see the number of inconsistencies that exist in the case. Figure One was part of a motion to suppress evidence. It was projected on screen during oral argument and could just as easily have been inserted into written motion papers.

In Figure One, the statements are presented in order of importance to the central issues in the case. The chart encompasses both inconsistent statements and omissions.2 Visually demonstrating the volume of inconsistent statements makes it much more difficult for the judge to explain away one example or another.

Impeachment goes far beyond the confines of inconsistent statements. Explore all of the ways in which an officer’s testimony can be different from the truth, including the following: testimony in conflict with other officers; testimony in conflict with civilian witnesses; failure to corroborate assertions with investigation; omissions; conflict between statements and physical evidence; statements in conflict with what the officer claims to have observed; and assertions that are not reasonable in light of the facts or the situation in which the officer found herself. These facts could go into a chart or summary similar to Figure One. The point is that inconsistencies should be hunted on cross and gathered in argument.

Exploring Witness Bias

While impeachment shows how the witness’s story has changed, bias tells us why it has changed. Unless an officer has a poor memory, a reason exists that his story is inconsistent with prior testimony, other witnesses, physical evidence, etc. It is incumbent upon the defense to posit to the factfinder why the story changed — to show that the inconsistency is born not of an innocent failure of recollection but rather from a mistake or even a willful falsehood. Did the officer suddenly describe the robber differently after the victim identified the accused in a show up? Was there a meeting with the prosecutor in between the officer’s police report and his grand jury testimony? Did the officer consult with his peers just prior to testifying to a different and more consistent version of the facts at the motion hearing?

Sometimes the explanations are innocent: the officer realizes his report is incomplete; the officer really does not remember what happened; or the officer met with the prosecutor or fellow officers to discuss what was important about the case. Sometimes the reasons are malicious. Even if the reason is just that as a police officer the witness has an interest in convicting the client, there is a reason for him to testify in a certain manner.

Bias is a story. It is a story about why a person testifies in a particular way. There is a bias story whether the witness’s testimony remains static or changes over time. To borrow a classic question from method actors, defense attorneys should always ask themselves, “What is this character’s motivation?” and think of ways to develop their questions and arguments around witness bias.

Police officers are human beings. They are subject to the same motivations that move everyone else — love, hate, greed, jealousy, anger, etc. Defense counsel may have cases in which one of these becomes an officer’s inspiration to act. There are forms of bias, however, that police officers can exhibit due to their work, and it is most often that these become fodder for a story of bias in cases. An officer’s bias can flow from his position; alignment with the State’s goals; desire to solve the crime; motivation to get promoted or otherwise advance his career; need to prove his value as a rookie officer; need to lay low and not ruffle feathers close to retirement; relationship to the alleged victim; negative feelings towards the accused; prior experiences with the accused; desire to catch the perpetrator under pressure; attempt to cover up a failure to follow departmental procedures; loyalty to another officer; anger at the suspect or the crime itself; history of excessive force or misconduct; or self-preservation to avoid disciplinary action. Even when no other bias is evident, an officer is always an agent of the government — the same government trying to convict defense counsel’s client.

Take a case in which multiple officers observe a hand-to-hand transaction but it is the rookie officer who outruns his fellow colleagues in blue to pursue and capture the client. The client tells defense counsel that he was just minding his own business when an officer tackled and arrested him. The rookie is the only officer who can testify that the man he observed is the one he put in handcuffs and, thus, the case rises and falls on his identification. In a case like this, it is important not only to cross-examine and argue any inconsistencies, omissions and unreasonableness in his account, but also to tell the rookie officer’s story of bias. It may include his time on the job, respect for fellow officers, the need to prove himself, how the weight of this case is on his shoulders because he is the only identifying officer, and how the weight of solving the case transferred to him when he outran his senior colleagues during the pursuit. By putting himself out in front, he became solely responsible for making sure the charges stick. The officer’s relationship to other officers enhances his motive to identify the accused. Every facet of that story is a chapter of cross-examination. The officer’s desire to prove himself to his peers is his story of bias. Bias diminishes credibility.

Commenting on Demeanor

The human brain is wired to instinctively process complex nonverbal cues. Dr. Albert Mehrabian, author of Silent Messages, conducted several studies on nonverbal communication in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He found that seven percent of any message is conveyed through words, 38 percent through certain vocal elements, and 55 percent through nonverbal elements (facial expressions, gestures, posture, etc.).3

In 2014, researchers at Ohio State University used computer models to discover that the human face can make more than 20 distinct facial expressions, a figure more than three times the “basic six” expressions noted by researchers in previous studies.4 Without thinking about it, people recognize these expressions and they communicate the emotions — and a gut feeling about the truth — another person is experiencing. “Our emotions influence every aspect of our lives. … Our emotions also influence how we connect with one another.”5 Add to a person’s facial expression the gestures, posture, tone of voice, mannerisms, and physical relationship to others in the same space, and the result is a person’s demeanor — a complete yet totally nonverbal way to assess credibility.

Demeanor is fundamental to human communication, but defense attorneys rarely observe, take note, and talk about it in courtrooms. By recognizing nonverbal communication and connecting judges to it, the defense opens up what is possibly the most undervalued source of credibility arguments.6

Judge Learned Hand recognized this as far back as 1952:

The [factfinders] may, and indeed they should, take into consideration the whole nexus of sense impressions which they get from a witness. Moreover, such demeanor evidence may satisfy the tribunal, not only that the witness’ testimony is not true, but that the truth is the opposite of his story; for the denial of one, who has a motive to deny, may be uttered with such hesitation, discomfort, arrogance or defiance, as to give assurance that he is fabricating, and that, if he is, there is no alternative but to assume the truth of what he denies.

Dyer v. MacDougall, 201 F.2d 265, 269 (2d Cir. 1952).

Human beings are walking credibility meters, and thus defense counsel does not need any special training to incorporate a witness’s demeanor into regular practice. All defense lawyers have to do is open their eyes. Defense counsel needs to put her pen down, turn her gaze to the witness stand, and look at the officer sitting there. Observe the witness. Note his facial expressions, body language, and gestures. Listen not only to his words but also to the tone of his voice, his choice of words, and the length of his pauses. Note if his tone is in contrast with his body language at certain times. For example, if an officer screams in an aggressive tone, “I am calm!” you can later argue that his demeanor belied his words.

Take note of these things once again when it is the defense’s turn to ask the questions. Notice if the officer behaves differently when the defense lawyer, as opposed to the prosecutor, is the one in control. Notice if the tone is different, the eye contact less constant, or the attitude less respectful.

Trial lawyers develop their own ways of keeping track of what witnesses say on direct and cross-examination. Lawyers should be as vigilant about keeping track of how the witness says it. The defense lawyer should create a witness demeanor checklist, take it to motion hearings, and use it to record what he observes. This could be as simple as a space in the margin of his trial notebook where he lists the following words: facial expressions, body language, gestures, and tone. Defense counsel should leave a space next to each word to remind himself to record his observations. Also, it is important to write down when changes occur. If an officer’s demeanor suddenly shifts or his tone and expressions become incongruent, counsel should note the precise question or subject matter that provoked the change so that he can develop arguments and cite to the transcript later.

Make demeanor a regular part of argument. Consider this argument: “The officer didn’t seem to be telling the truth about knocking and announcing his presence.” Does it mention demeanor? No. This argument is better: “Your honor, every time I asked the officer a question about announcing himself, he looked down into his lap and his voice went from loud to soft. I noted five times when this happened. Here are the page and line numbers where that occurred.”

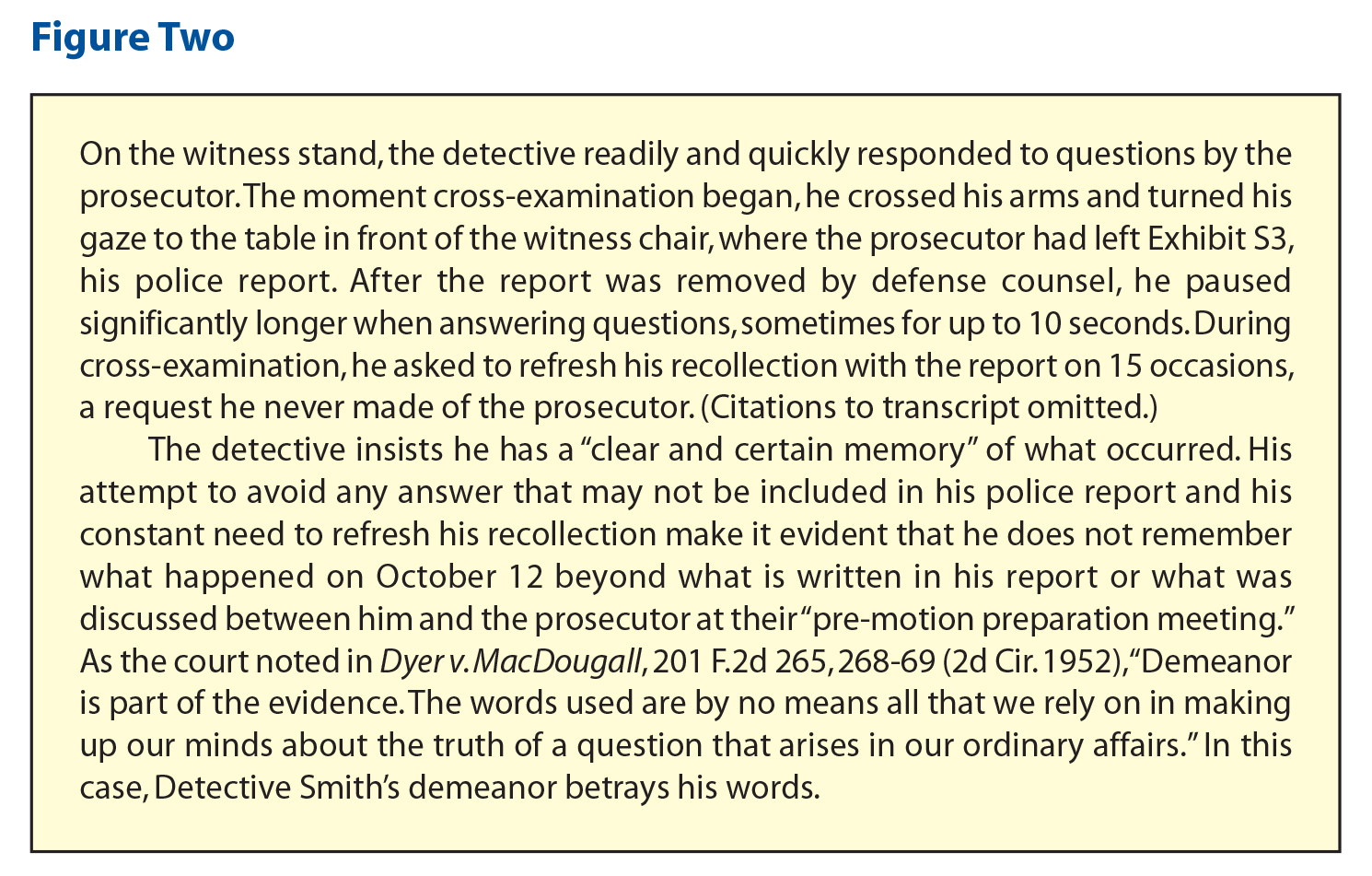

Figure Two is an example from a motion to suppress physical evidence in which a critical issue for defense counsel was the detective’s ability to remember events undocumented in the police report.

Demeanor is the most underused weapon in the defense team’s credibility arsenal. It is high time attorneys started to make it a regular part of motion practice.7

Applying Systemic Arguments

The United States is in the midst of a new civil rights movement. People everywhere are talking about racial profiling, implicit bias in policing, and police misconduct. The good news is that these important issues are permeating the public consciousness in entirely new ways. The bad news is that systemic issues are difficult to argue in court because they require the factfinder to take statistical evidence and apply it to individual cases. It is uncomfortable to talk about race and the justice system, and the truth is that courts across America do their best to avoid it.

In some cases there is a cognitive dissonance — an uncomfortable feeling of holding two simultaneously contradictory thoughts or beliefs — when implicit bias is brought up in court.8 A judge may be confronted with a case in which racial bias is evident but at the same time may be reluctant to say that the officer sitting next to him on the witness stand in the flesh, perhaps one he has seen before and will see again, engaged in such conduct.

Psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon described cognitive dissonance as applied to race in this way:

Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn’t fit in with the core belief.9

For advocates who day in and day out hear stories from clients of color about the way police interact with them, the idea that an individual officer acted with implicit or even explicit bias is easily accepted. This concept may be more difficult to accept by a prosecutor or a judge who, regardless of his race, does not regularly sit with and speak to criminal defendants about their experiences with police. Although it is not wise to presume to know what anyone’s journey in life has been, when it comes to being a judge, membership has its privileges. It is only human for people to view the world through the filter of their own experiences, and such a view does not typically inure to the benefit of the accused. The hurdle to overcome is to establish the link between the larger social justice problem and this client in this case.

Criminal defense attorneys must be mindful that most laypeople do not make the leap from smoke to fire in these situations quite as quickly as attorneys do. The defender inside wants to scream, “You honor, it is obvious that the officer pulled this man over because he is Hispanic!” but doing so does not often advance the case. It may actually set the client back because it quickly puts the judge in the difficult position that any ruling in favor of the defense supports an inflammatory and yet, in this example, unsubstantiated accusation.

Cognitive dissonance theory is based on the idea that human beings are sensitive to inconsistencies between actions and beliefs and highly motivated to resolve dissonance when it occurs.10 When an attorney accuses an officer of racial bias in the courtroom, it usually causes a kneejerk conflict for the judge between the larger social justice problem that exists and the uncomfortable feeling of having to apply it in the case before him even when the case is strong. This is dissonance.

Anyone who has engaged in politics on social media these days knows that the worst thing a person can do to confront another’s dissonance is to put him in a position in which he is forced to defend his beliefs. In a 2003 study on attitudes about the death penalty, researchers at Duke University discovered that “[a]ttitudes are most likely to change when there is relatively little public discourse on issues, rather than when a public dialogue forces people to defend, and thus reinforce, their own beliefs.”11

Psychologists who study cognitive dissonance say that it will ultimately be resolved in three ways: (1) rationalization, (2) aversion, or (3) a change in beliefs.12 Lawyers most often get rationalization — courts that work hard to explain away the facts that support the defense’s allegations. Aversion is a double-edged sword. Sometimes courts just ignore the most difficult arguments, but sometimes they grant the motion on another issue to avoid reaching the tough stuff. In short, defense attorneys want to avoid rationalization and can sometimes live with aversion, but as so often is the case in the legal arena, it is change they are really after.

How does one get it? Not through confrontation. The goal is to open the courts to the discussion — to make it comfortable or at least tolerable to listen. This takes a slow and steady approach that allows the person experiencing the dissonance to come to the desired conclusion on his own. Using the tools available in the courtroom, defense lawyers can better persuade factfinders to turn to the defense’s way of thinking on seemingly difficult issues by establishing every fact — big or small — that supports the assertion, building the facts in progression towards a logical conclusion, and giving the factfinder the space to get there in his own way.

Establishing the facts that will allow the defense lawyer to connect her case to the larger issue is easier said than done. Facts supporting, for example, an argument that an officer engaged in racial profiling are rarely grouped together in the testimony and exhibits, otherwise it would be much easier to prove. Look for any evidence in the record and isolate it with laser-like precision. Go through transcripts, videos, and written materials. Study the officer’s and the accused’s body language and tone in dash cam recordings and taped statements. Use all the tools discussed thus far to fully develop the case.

When she moves to the argument, the defense lawyer should build the facts slowly in progression towards the conclusion she wants the factfinder to reach by going from her weakest argument to her strongest. Unlike inconsistent statements, where one wants to go from the strongest to the weakest argument to combat the factfinder’s temptation to excuse the minor differences in testimony, building systemic arguments from weakest to strongest allows the factfinder to work with his natural cognitive dissonance until the dissonant facts (or facts that tell the defense story) become too powerful to ignore. If the lawyer does it well, the factfinder will come to the conclusion she wants him to reach on his own.

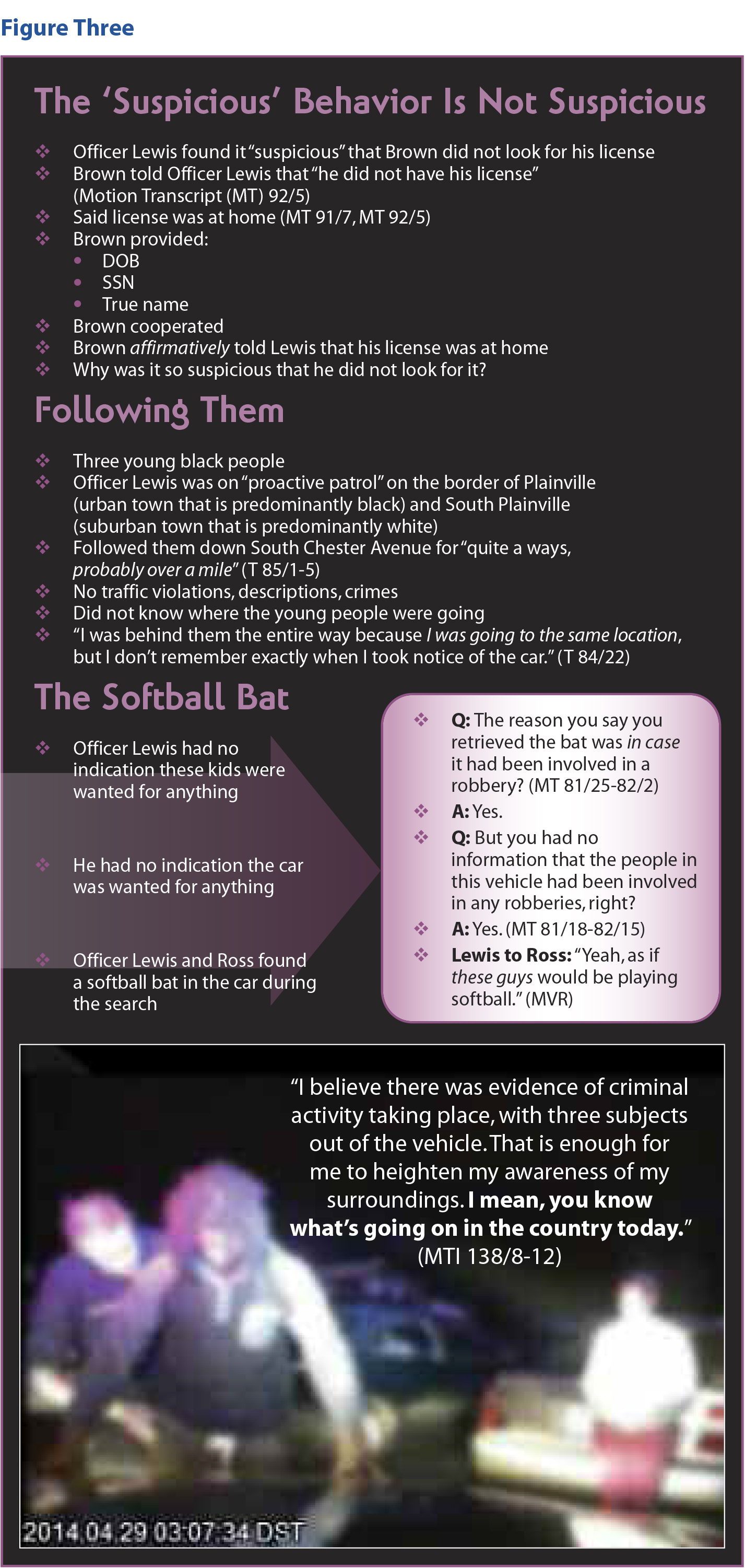

Figure Three is part of a motion to suppress physical evidence in which one of the chief defense arguments was that defendants were pulled over not for a traffic violation but for “driving while black.” The case involved three lawyers, three days of hearings, at least three dash cam videos, and testimony from four police officers. The three days of testimony occurred over a six-month period. Suffice it to say, the facts underlying the case did not come all at once, from one place, or through one witness.

The facts supporting racial profiling were as follows: the officer followed the three young people from an urban town into a suburban one; the officer followed them for more than a mile for no reason; the officer found a softball bat in the car and admitted that it was unconnected to any crimes; later in the stop, the officer commented that “these people” had no reason to be in possession of a softball bat; and the officer called it “suspicious” that the driver did not look for his license despite the fact that immediately after being pulled over, the driver told the officer he left his license at home. This is not the greatest case for racial profiling. None of these things individually were a smoking gun, but the collective impact suggested profiling was afoot.

The first step was to gather the facts needed to support the conclusion during cross-examination. The facts were intentionally not developed in one section of the cross but spread out over the course of the hearing. The attorneys did this to avoid putting the judge’s back against the wall too early in the process.

In oral argument, the attorneys used a PowerPoint so that they could connect visual elements like the dash cam video to the testimony elicited at the hearing. Figure Three includes the slides used in the oral argument.

All the facts gathered sporadically during the motion hearing were finally grouped into one section. The attorneys used video stills, citations to motion transcripts, dash cam audio, references to police reports, and quotations of the officer’s own words to create the slides.

Unlike other areas of the argument where the attorneys would tell the judge “now we are going to address the issue of consent” or “let’s talk about the officer’s inconsistent statements,” they made no announcement that they were about to build the case for racial profiling. They presented the facts from the weakest to the strongest. All of these decisions allowed the judge to ignore or to rationalize the less significant facts and avoided forcing the judge’s hand too early.

It is important to note that the officer’s comments on the last slide were in no way connected to the video still upon which it is superimposed. He did not speak those words while frisking the accused; he spoke them in court while explaining his “reasonable and articulable suspicion” to the judge. The still from the dash cam — a young black man forced to place his hands on the hood of a police car — was a powerful image that encapsulated the defense’s interpretation of the officer’s words. It was a way of using the officer’s words to support an argument that the problem in America today is that too often it is young black men who get stopped by police without justification.

Although the information came in sporadically over days of testimony and months in between hearing days, it was culled and packaged in one section of the motion argument. Arguments were advanced step-by-step from weaker to stronger. By the time the argument ended, the prosecutor jumped out of his chair in outrage. The judge overruled his objection and agreed that the facts supported an inference of profiling. Ultimately, the judge did not grant the motion. The court did grant a different motion that resulted in the dismissal of the most serious charges in the case. When change of mind does not succeed, sometimes aversion will do.

There is an important final thought on this issue. Lawyers should not have to tiptoe around the issue of racial bias in policing. Defense lawyers have a duty to speak up and speak out about injustice no matter how uncomfortable, unsafe, or unwelcomed it may be. That said, when appearing in court on a motion, defense lawyers have a client sitting beside them — a human being whose life and liberty depend almost entirely on how they proceed. In that moment, the lawyer’s personal anger, outrage, or disgust about what he sees in a case should be the fuel for his fire to succeed, but these feelings may have to take a backseat to the best approach to the circumstances and the courtroom in which the lawyer finds himself. The approach outlined here is based on the psychology behind bringing people around to new points of view and is offered as a guide for arguing systemic issues to factfinders who may not be immediately receptive. Although the suggestion could be used in other settings, it is by no means a definitive guide of how lawyers should behave when they have a different platform for speaking out. When the time is right, they should be as bold and as loud and as vocal as they can be!

Arguing Noncompliance

Police officers love rules. There is an operating procedure for everything. Uncovering, studying, and holding officers accountable for noncompliance with these rules can provide fertile ground for cross-examination, may uncover bias, and can create compelling arguments.

The rules are discoverable, and defense attorneys must ask for them. Use Freedom of Information Act requests (FOIA), local equivalents to FOIA, listservs, and good old-fashioned internet searching to collect police department standard operating procedures. If something looks even vaguely like a rule, collect it. Find the state’s attorney general guidelines and other directives that spell out the standard of conduct expected from officers in the field. File Brady motions that force prosecutors to ask their officers for such guidelines.13 Discover training manuals, handbooks, and academy training curricula. Ask other attorneys if they have copies of these materials. An attorney should share his materials with other attorneys unless he is specifically prohibited from doing so by a protective order. The bigger an attorney’s database of police procedures and training materials, the more ammunition he has to make noncompliance arguments.

Furthermore, endeavor to find out what happens when an officer fails to follow a guideline, training directive, procedure, etc. Know the state’s law enforcement disciplinary process, the levels of discipline used to punish violations, and how that process works.

When preparing to cross-examine an officer on standard operating procedures, first establish that the officer is aware of them and trained on them. The defense lawyer should begin here before the officer knows where he is going with his line of questioning. Once that is out of the way, elicit the facts that are relevant to the procedure. Confront the officer with the violated procedure when it is too late for him to come up with an excuse for his misconduct. Showing that an officer did not comply with a rule gives the judge a fact-based way to discount officer testimony. A judge does not have to opine on an officer’s lack of credibility if he can hang his hat on a procedure the officer failed to follow.

When preparing to cross-examine an officer on standard operating procedures, first establish that the officer is aware of them and trained on them. The defense lawyer should begin here before the officer knows where he is going with his line of questioning. Once that is out of the way, elicit the facts that are relevant to the procedure. Confront the officer with the violated procedure when it is too late for him to come up with an excuse for his misconduct. Showing that an officer did not comply with a rule gives the judge a fact-based way to discount officer testimony. A judge does not have to opine on an officer’s lack of credibility if he can hang his hat on a procedure the officer failed to follow.

Another way to use the standard operating procedures is to establish bias. Sometimes failure to comply with more serious procedures can result in discipline, suspension, or even termination. In such cases, an effort to cover up a violation of a procedure may become defense counsel’s story of witness bias.

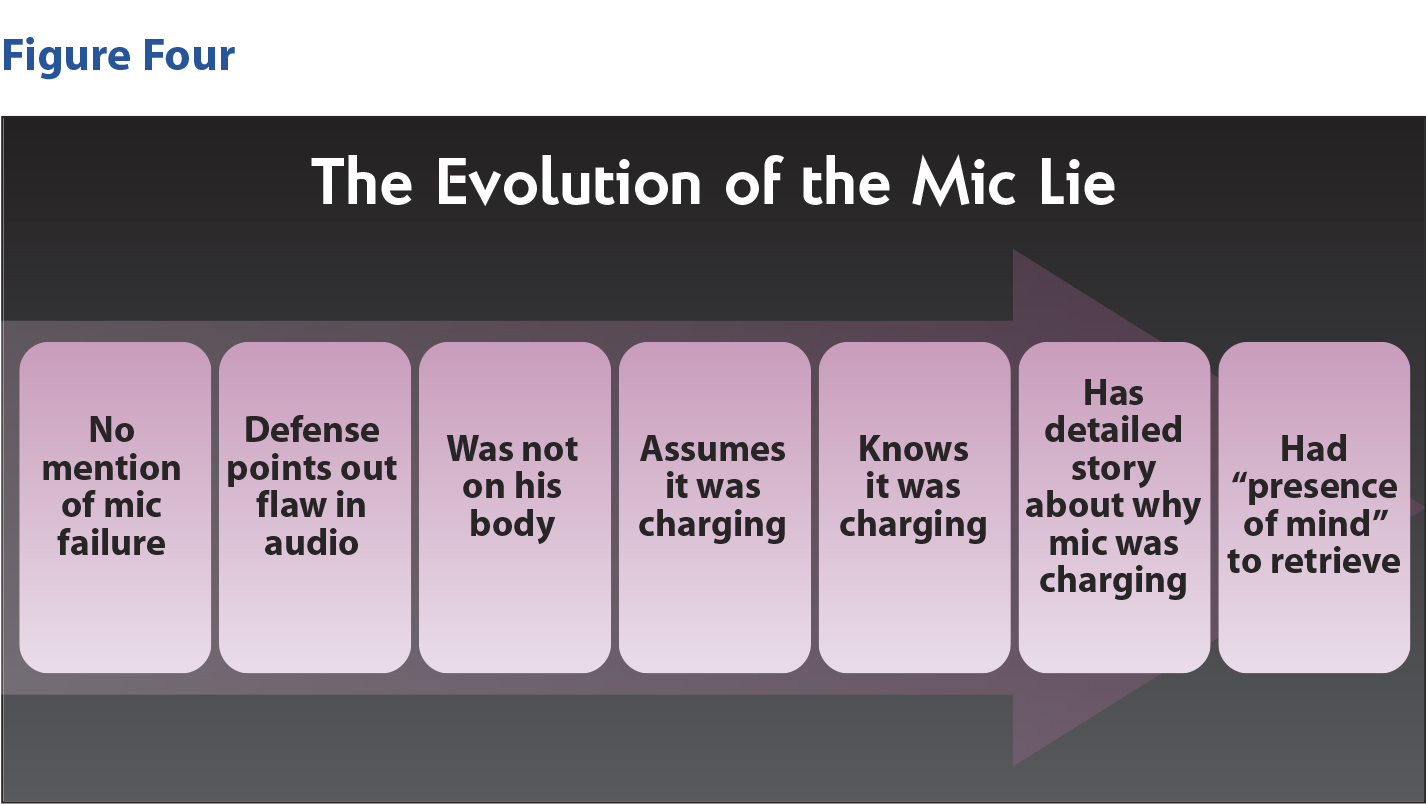

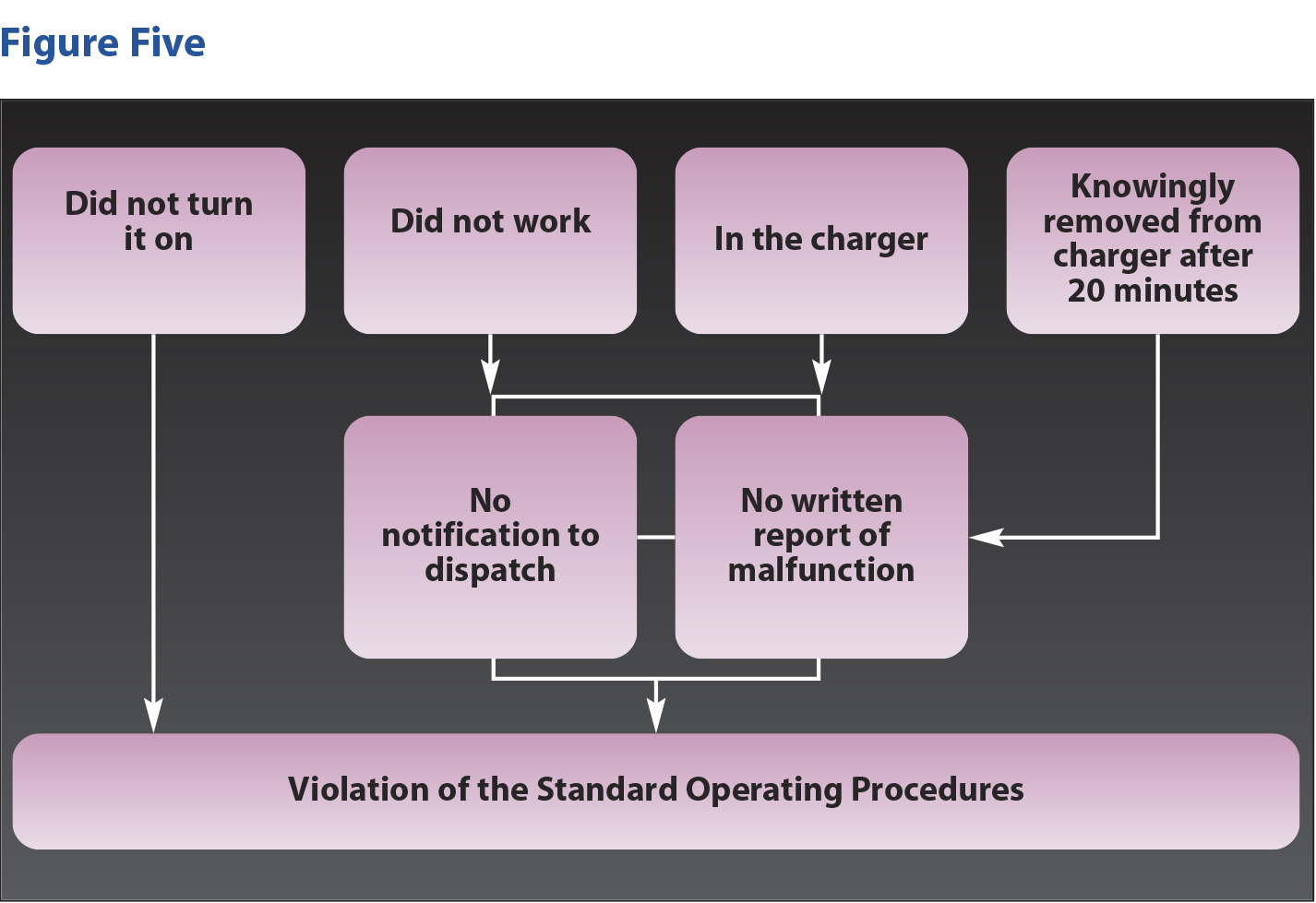

Figure Four and Figure Five are examples from the same racial profiling motion discussed earlier. The issue was that the audio portion of the officer’s microphone cut out at key moments on the dash cam video. Rather than argue that the officer intentionally turned off the microphone, something that was tempting but would require the judge to call the officer a liar, the defense argued that the reason the microphone cut out did not matter because, no matter which of the officer’s changing explanations the court accepted, he nevertheless violated the department’s standard operating procedures.

Figure Four, the image with the big arrow, showed the officer’s changing testimony about the missing audio.

Figure Five uses a flowchart to visually illustrate to the judge that not one of the officer’s seven excuses passed muster under the department’s standard operating procedures.

Knowing the rules and using them against officers that violate them is one of the few objective measures of credibility.

Telling Stories

In her book Wired for Story, Lisa Cron refers to story as a part of human evolution. When people hear stories, their brains ignite. More areas of the cerebral cortex activate when people hear a story than when they hear someone recite a list of facts. The brain releases dopamine, the same substance released when people experience emotionally charged events. Neural coupling allows the listener to turn the story he is hearing into his own experience, thereby allowing for an emotional connection between the storyteller and the listener. The listener’s brain activity mimics that of the storyteller.14

Stories move people to action more than anything else. In 2006, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania studied something called the “identifiable victim effect.”15 The study involved a subject’s likelihood of donating money to a cause based on the method in which the cause was explained. Subjects were shown statistics alone, the personal story of an “identifiable victim” who would benefit from the donation, or both an “identifiable victim” story and statistics. Subjects who saw only the “identifiable victim” story gave more than double the donation than those who saw statistics alone. Perhaps more surprising, donations for the “identifiable victim” story were more than double when compared to the situation in which researchers combined the story with the statistical data.

The lesson? Make it personal.

Advocacy has evolved to the point where storytelling at trial is second nature; however, advocates are far less proficient storytellers at motion hearings and arguments. By taking everything they have learned about storytelling and trial and applying it to motion hearings, defense lawyers obtain a powerful tool for confronting officer credibility: the client’s own experience.

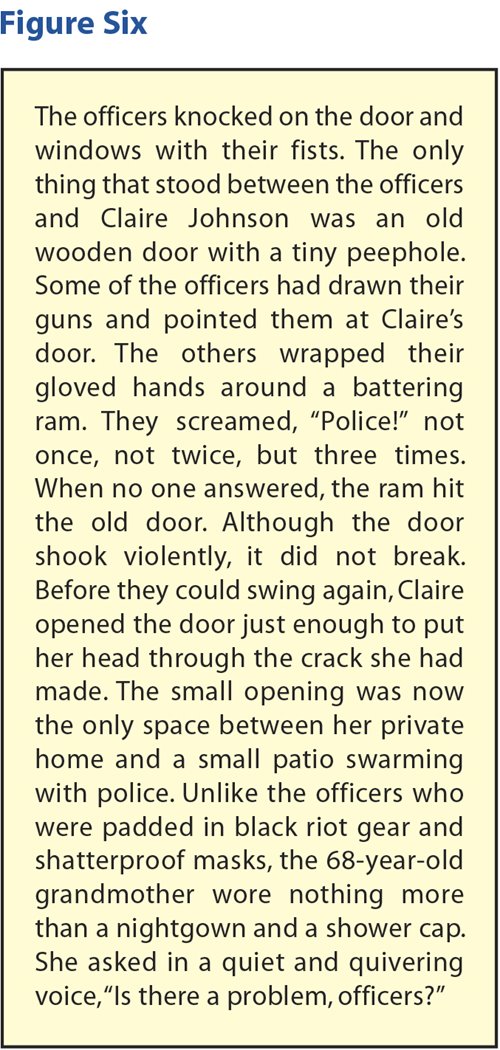

Sometimes defense lawyers must force the judge to look at the facts through the client’s lens. Consider, for example, a case in which the defendant’s argument is that she did not consent to the search of her home. A brief may read like this: “The officers knocked on the door three times and announced their presence. After several minutes, the occupant opened the door and asked them if there was a problem.” While these facts may be true, they neither capture the client’s experience nor create the feeling of a situation in which she felt free to refuse consent.

Push past the paper, brainstorm with the client, and think about the encounter from the client’s point of view. Ask these questions:

- How many officers were present?

- How big were they?

- What were they wearing?

- What was their position?

- How were the officers dressed?

- Were their guns out?

- What was their tone?

- What were the exact words spoken?

- What time was it?

- When did they knock?

- How many times did they knock?

- What did each knock sound like?

- How fast did those knocks come?

- Were the knocks hard, soft, or did they change?

The most important questions invite the client to engage all her senses to relive the experience. They are always the same:

- What did you see?

- What did you hear?

- What did you smell?

- What did you taste?

- What did you feel?

It may seem absurd to ask the client what she smelled, tasted or felt in a situation like the one described, but pushing people to remember less obvious senses may be surprisingly useful. In this example, the accused told the attorney that while she was standing behind the door she felt vibrations through the floor, which led to confirmation at the motion hearing that a battering ram had been used to knock at the door. Engaging the senses, even if the client is not going to testify, helps counsel create a narrative and ask questions on cross-examination that allow the judge to see the events from the client’s point of view.

After getting a picture of what the client may have experienced, defense counsel should articulate these ideas in the written motion and in the oral argument. While staying true to the facts, counsel can create his own narrative, as shown in Figure Six.

The revised version is the mental picture the defense wants the court to see. The reader feels the emotions this woman may have felt when overcome by police. The second version also evokes what Claire Johnson may have seen through the peephole without introducing a single argument predicated on calling her to the stand.

Arguments this like one require that defense counsel do the work up front so that counsel knows what details to elicit on cross-examination. For example, the cross would need to include that the door was old and had a peephole, details of what the officers were wearing, and Claire’s nightgown and shower cap — details that may seem meaningless to the legal issues. Telling stories requires lawyers to know what they want to argue — both legally and creatively — so they can ask the questions that get them there.

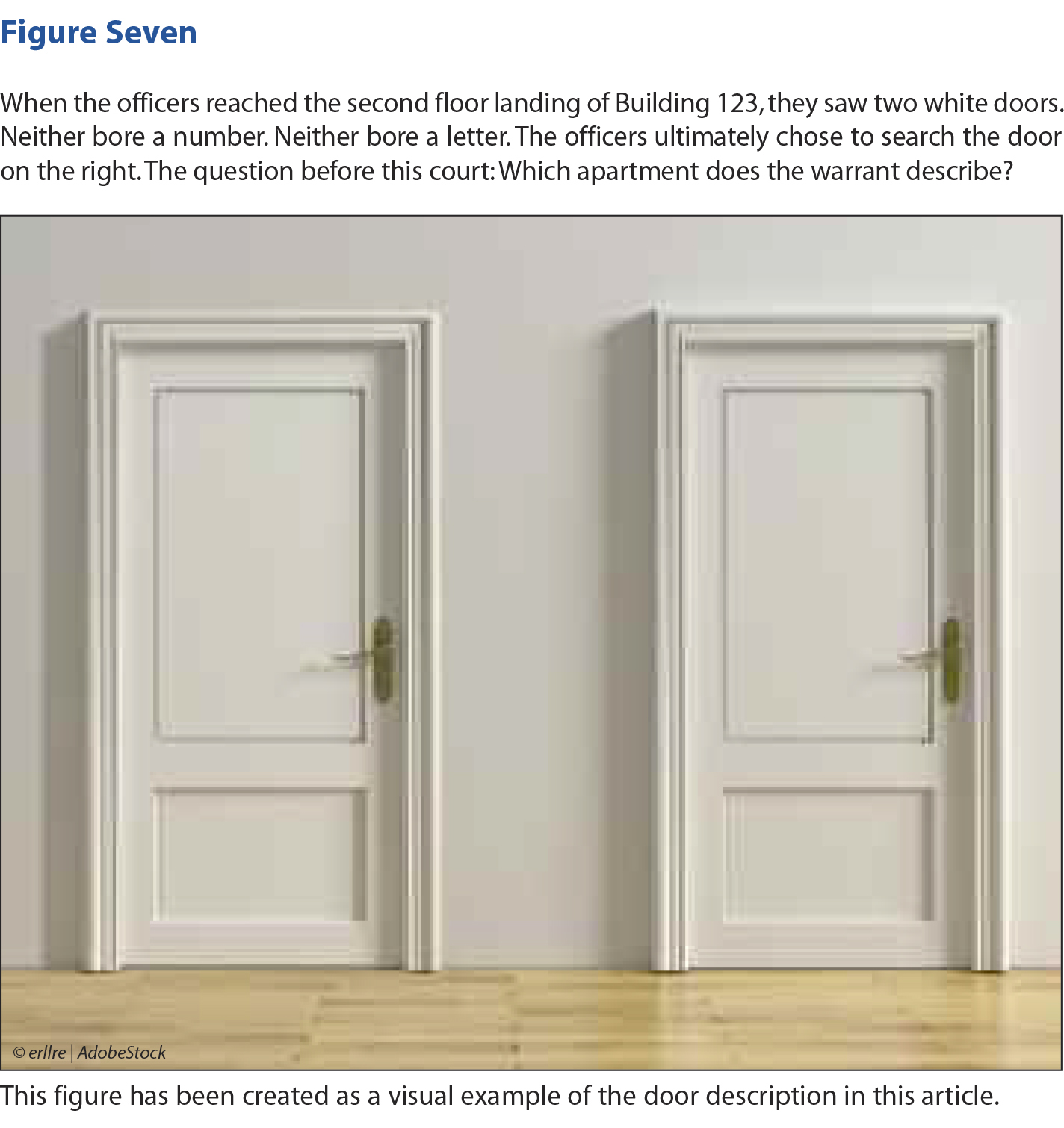

Searches with warrants are some of the most difficult to bring to life because the defense does not have the benefit of an evidentiary hearing. Consider a challenge to particularity. Take the warrant, go to the scene, walk around, and ask one question: “With only this warrant in my hand, would I know where to search and what to look for?” If the answer is “no” or even slightly unclear, the defense lawyer has an argument. How can counsel bring this argument to life? Counsel does it by helping the judge see the space in the same way that counsel did. Use video, Google maps, photographs and, of course, storytelling.

Figure Seven is part of a sample fact section from a motion to suppress a search made pursuant to a warrant. The warrant described the premises as an apartment located at 123 Main Street, Apartment #25, on the second floor, with a white door. On paper, the warrant appears to contain an accurate and detailed description. Going to the scene was a different story — a story that resulted in the motion to suppress shown in Figure Seven.

By showing the court what the officers saw when they walked up the stairs, it becomes immediately apparent that the search was a guess that required the officers to choose between what was behind door #1 and what was behind door #2. Sometimes storytelling means putting the defense attorney — and ultimately the judge — in the position of the officer.

Combining Visual Aids With Storytelling

“The story is what creates the beautiful writing, not the other way around.”16 The same is true for legal writing. Lawyers cannot manufacture a story; they must discover it. By reviewing the materials provided by the State for impeachment, thinking about witness bias, investigating, standing at the scene, observing the witnesses, listening to the client, and making connections to systemic issues, lawyers begin to unearth the story and the shape of each motion.

This article contains several examples of visual techniques to challenge police testimony. It is important to remember that these visual aids must also be combined with storytelling. The purpose of the visual aids is to enhance, not replace, the most essential parts of the story.

Begin with the story before conceiving of visual aids. Think carefully about the words and phrases to be used in the fact section of the motion and about the structure and form of the legal argument that follows.

Pretend that the fact section is an opening statement. Begin with the facts that make up the scene that is most critical to the legal argument regardless of when that scene takes place in the order of events. Avoid chronological order and reciting facts like a list. Put the reader in the middle and finish strong. If necessary, circle back to the chronological order as the fact section continues.

Be intentional. Consider word choice, sentence structure, tense, choice of active or passive voice, etc. Every sentence and every word must serve a purpose. Every word must drive the story.

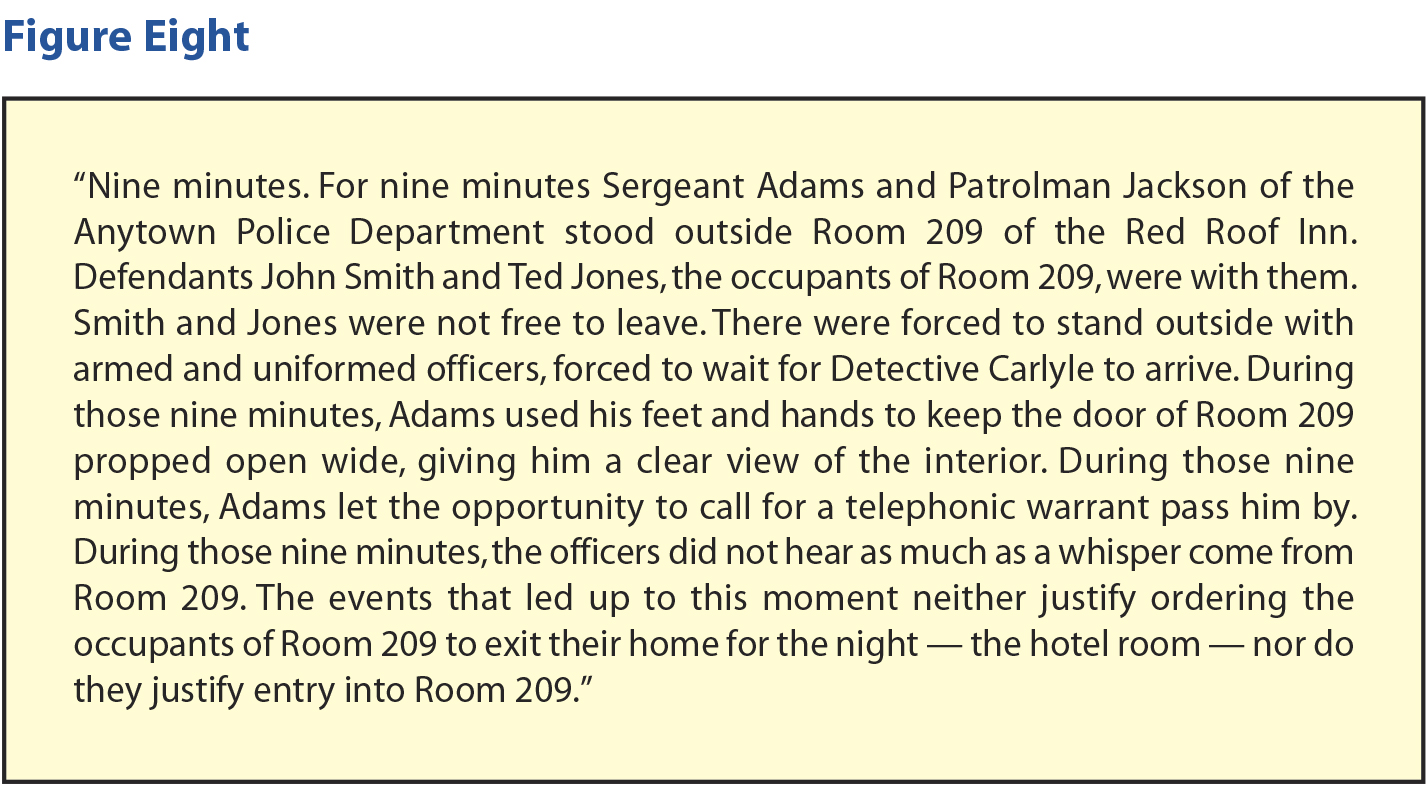

Figure Eight is an example of the fact section in a motion to suppress. The key issue was what happened after officers ordered two men out of a hotel room and waited for back up to arrive.

Using storytelling to capture and maintain the reader’s interest, Figure Eight’s one-paragraph fact section hits every legal argument the defense will make in the pages that follow. It contains a catchy introduction and a clear theory. The fact section intentionally uses the passive voice to show that the defendants had no control over what the officers were doing to them, and the fact section creates word pictures to paint a scene in the judge’s mind of what that critical moment in the case was like for the accused as it was happening.

When it is time to continue to the legal argument portion of the brief, the same principles apply. Start with the crux of the argument and then structure the arguments in order of importance. Do not begin the legal argument at the beginning; begin with what is most important to the determination the defense wants the judge to make. Start with the following:

- the best legal argument

- the portion of the stop when everything changes (usually where it takes a negative turn for the client)

- a quote from a person in the case

- a great description of the physical scene

- the biggest bone of contention with the State’s argument

Avoid beginning with a quote from case law unless it is so dispositive of the case that it is more important than anything else. As one can analogize from Small, Lowenstein and Slovic’s identifiable victim study referenced above, case quotes are impersonal and therefore less useful in the art of persuasion.17

The golden rule of primacy and recency is always in effect. This principle says that people are more likely to believe the first thing they hear and more likely to remember the last. Defense counsel wants the judge to both believe and remember the defense’s best argument. Lead with it, and end with it.

After writing the fact section and the legal argument, consider visual aids. The approach lawyers take and visual aids they choose are dictated by the story, not just their desire to do something creative. Use the tools discussed thus far to replace lists of facts with charts or diagrams. Insert pictures to highlight locations or photographs that are important to the defense team’s argument. Include video stills or portions of transcripts. The attorney can also insert audio and video files into written motions so that the factfinder can click on them when the attorney wants to highlight them in the brief. The only limit when it comes to audio-visual aids is counsel’s own imagination.

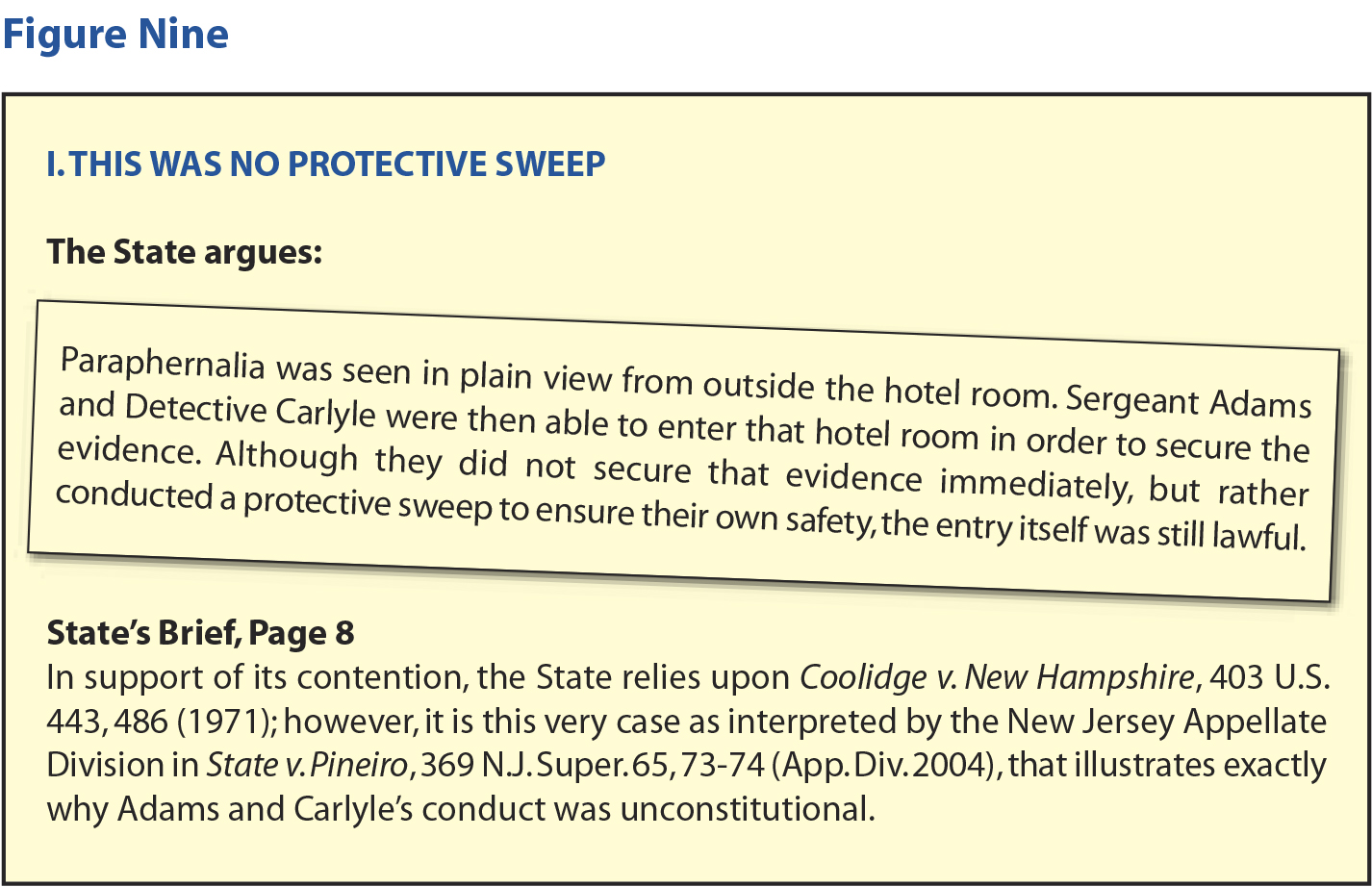

Figure Nine is an example from the legal argument section of the same hotel-search motion. Here, the attorney attempted to show that the legal principle on which the State was relying was completely wrong. The portion taken from the State’s brief is intentionally set cock-eyed to visually tell the judge something is wrong with it and, again, to make the judge interested in reading it.

Finally, consider using demonstrative aids during oral argument. Supporting an argument with a presentation is more interesting, keeps the court’s attention, and signals to the court that counsel is serious about and prepared for the argument. If counsel uses a presentation, it should enhance the argument rather than replace it, which means the slides should be comprised of more pictures and audio than words. Do not create slides with case law on them or turn the legal brief into a boring, text-laden slideshow. The presentation is just the medium for organizing and displaying visual and audio aids.

What is the most dangerous phrase in the English language? Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, an American naval officer and pioneer computer programmer, reveals the answer in her famous quote: “We’ve always done it that way.” Making the arguments and using demonstrative aids in the way discussed above may be foreign, may be new, and therefore, may be a source of anxiety. It is only natural to feel nervous about trying some of these techniques in a courtroom. That is precisely the reason defense counsel should do it.

When defense lawyers walk into a courtroom with a fascinating visual presentation, they will find rooms that suddenly stand still. Courtrooms will stand still because people, especially judges, are interested in what the lawyers have to say. Holding that attention is both thrilling and terrifying, but if lawyers can get over the fear that naturally comes with doing something no one has ever done, they will be handsomely rewarded. They will break up the daily doldrums of the courtroom, and most judges will appreciate it. Judges will start giving defense counsel extra time for argument. Most importantly, judges will want to hear what counsel has to say next.

Conclusion

Breaking down the credibility of a police officer before a lone judge at a motion hearing is one of the most difficult tasks defense lawyers face. It is also one of the most fun. There is no other arena — not even a trial — where defense lawyers feel the full weight of the government bearing down on them. There is no jury and few onlookers; it is just defense counsel against the overwhelming power of the State. In those moments, defense counsel becomes the living, breathing embodiment of the Constitution. In those moments, the State must go through the defense lawyer to get to the client. In those moments, the defense lawyer is David to the government’s Goliath. The suggestions outlined in this article give defense counsel a little more ammunition to aid in the fight. And maybe, just maybe, defense lawyers can now replace the pebble in their slingshots with that rock they have heretofore been pushing up the hill.

Notes

- Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690 (1996); Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983); Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160 (1949).

- The blank spaces represent places where, for strategic reasons, nothing pertaining to the point was brought out on cross-examination. Boxes that indicate “nothing” are points on which the officer was impeached by omission during the hearing.

- A. Mehrabian, Silent Messages: Implicit Communication of Emotions and Attitudes (1972). Subtracting the seven percent for actual vocal content leaves one with the 93 percent statistic.

- Shichuan Du, Yong Tao & Aleix M. Martinez, Compound Facial Expressions of Emotion, Ohio State University, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2014).

- Rana el Kaliouby, Ted Talk published Oct. 1, 2015, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8_Ry7KRzjTY&t=11s. Rana el Kaliouby is an American computer scientist, entrepreneur, contributor to facial expression recognition research and technology development. She is the founder and CEO of Affectiva.

- Thanks and acknowledgement to the Honorable Judge Michael Ryan of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. His presentation, “Arguing Witness Credibility,” inspired this portion of the article.

- Although the citations to transcripts in this and other examples have been omitted for publication, their inclusion in practice is critical. Citations are a way of connecting the demeanor to specific words and points in time.

- Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957). The psychological phenomenon of cognitive dissonance was first coined by Festinger in 1957.

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952). Although Fanon used the term cognitive dissonance in his earlier work on the theory of race and racism, the condition of cognitive dissonance as applied to general psychology is attributed to psychologist Leon Festinger.

- Psychology World, referencing Leon Festinger (1957). Leon Festinger & J.M. Carlsmith, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1959); Leon Festinger & J.M. Carlsmith, Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance, 58 J. Abnormal and Social Psychol. 203-210 (1959).

- S.R. Gross & P.C. Ellsworth, Second Thoughts: Americans’ Views on the Death Penalty at the Turn of the Century, in S.P. Garvey (ed.), Beyond Repair? America’s Death Penalty 7-57 (2003).

- Psychology World, referencing Leon Festinger (1957). Leon Festinger & J.M. Carlsmith, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1959); Leon Festinger & J.M. Carlsmith, Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance, 58 J. Abnormal and Social Psychol. 203-210 (1959).

- Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963).

- Lisa Cron, Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide for Using Brain Science to Hook Readers From the Very First Sentence (2012).

- Deborah A. Small, George Loewenstein & Paul Slovic, Sympathy and Callousness: The Impact of Deliberative Thought on Donations to Identifiable and Statistical Victims, 102 Organizational Behav. & Hum. Decision Processes (2006).

- Lisa Cron website, http://wiredforstory.com.

- See note 15, supra.

About the Author

Jennifer Sellitti is Director of Training & Communications for the New Jersey Office of the Public Defender, where she is responsible for teaching trial advocacy and substantive law to public defenders. She also represents clients charged with felonies ranging from drug possession to murder.

Jennifer Sellitti

New Jersey Public Defender’s Office

Trenton, New Jersey

609-292-7087

jennifer.sellitti@opd.nj.gov