Access to The Champion archive is one of many exclusive member benefits. It’s normally restricted to just NACDL members. However, this content, and others like it, is available to everyone in order to educate the public on why criminal justice reform is a necessity.

With protests and civil demonstrations springing to life all over the country in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, it is distinctly possible we are witnessing the birth of the second civil rights movement in the United States since the 1960s. This was not the year I envisioned as president of NACDL. However, while national debate about police brutality, racial profiling and racial bias rages on, and virtual jury trials threaten to undermine the constitutional pillars on which the foundations of justice rely, I don’t want to leave office without turning my attention back to the inequalities suffered by women of all races and creeds in the criminal justice system that continue to go unnoticed and unabated. Indeed, as women represent a larger percentage of the casualties of the criminal justice system, it becomes imperative that they become stakeholders in the national dialogue — both to better meet their needs and to stem the tide of mass incarceration and broken families in this country.

Women as an Incarcerated Population

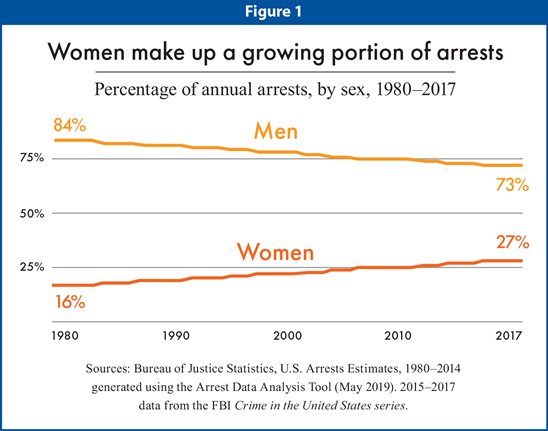

I began my term by trying to focus public attention on the fact that the number of women entering the criminal justice system has exploded in the past two decades. Women as a growing share of prison and jail populations have largely escaped public view. The number of women in jails across the United States has increased from approximately 8,000 in 1970 to nearly 110,000 in 2014, a 1,275 percent increase. Women are the fastest growing correctional population nationwide since the early 1990s.{1} 1 You Miss So Much When You’re Gone, American Civil Liberties Union & Human Rights Watch, at 2 (2018), available at https://www.aclu.org/report/you-miss-so-much-when-youre-gone. Though the total number of arrests in the United States has dropped by more than 30 percent, from 15.3 million in 1997 to 10.6 million in 2017, the decrease was due primarily to a decline in the number of male arrestees.{2} 2 Policing Women: Race and Gender Disparities in Police Stops, Searches, and Use of Force, Prison Policy Initiative (May 14, 2019), available at https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/05/14/policingwomen. During that same time, the number of women arrested only declined 6.4 percent. Consequently, women are continuing to comprise an increasingly larger share of the arrestee population within the United States.{3} 3 Id. Not surprisingly, the rising rate of imprisoned women has given the United States the “distinction” of having the highest rate of incarcerated women in the world.{4} 4 How the First Step Act Can Have Lasting Impacts on Women in the Criminal Justice System, Medium (Feb. 4, 2019), available at https://medium.com/the-new-leader/how-the-first-step-act-can-have-lasting-impacts-on-women-in-the-criminal-justice-system-752374249c7c.

It is important to realize that although women are comprising an ever-larger part of the prison population, they are being housed in a correctional system that was primarily designed for men. In 2018, the DOJ Office of the Inspector General (“IG”) authored a report detailing the failings of the Bureau of Prisons’ management of its female populations.{5} 5 Review of the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Management of Its Female Inmate Population, Office of the Inspector General — Evaluation and Inspections Division (Sept 2018), available at https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/e1805.pdf. The report starts out stating that the “BOP has not been strategic in its management of female inmates … resulting in weaknesses in its ability to meet their specific needs.”{6} 6 Id. at i. Among its findings, the OIG report identified three core issues:

First, we found that low staffing limits BOP’s ability to provide all eligible female inmates with trauma treatment, even though a study relied upon by BOP shows that approximately 90 percent of female inmates are affected by sexual, physical, or emotional trauma at some point in their lives.

Second, we found that only 37 percent of sentenced pregnant inmates participated in BOP’s pregnancy programs.

Third, not all prisons ensured that female inmates had sufficient access to feminine hygiene products.{7} 7 Report: Federal Prisons Fail to Provide Adequate Services for Female Inmates, Wash. Post (Sept. 18, 2018), available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2018/09/19/report-federal-prisons-fail-provide-adequate-services-female-inmates.

Since the OIG released its report, little has been done to improve the conditions for incarcerated women. On December 21, 2018, President Trump signed the FIRST STEP Act into law — a bipartisan piece of legislation that was designed to reduce recidivism among federal prisoners. It has been considered one of the “most pivotal criminal justice reforms of this generation.”{8} 8 Supra note 4. However, the FIRST STEP Act contains only two provisions that specifically target women’s issues: mandating that healthcare products, such as tampons and sanitary napkins, are provided free of charge and prohibiting restraints on women who are pregnant and who are in postpartum recovery.{9} 9 Id. Moreover, the FIRST STEP Act only applies to those women serving their sentences in federal institutions and does not improve conditions for women in state prisons or jails.

Indeed, this systematic inattention to women’s penal institutions (both state and federal) is having a profoundly deleterious effect on health outcomes for women prisoners during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women, a New Jersey Department of Corrections facility where federal investigators previously found that the state of New Jersey had failed to protect female prisoners from sexual abuse, COVID-19 is spreading because of low supplies of masks.{10} 10 COVID-19 Spreads in Women’s Prison Where Sexual Abuse Prompted Federal Probe, Say Inmates and Advocates, NJSPOTLIGHT (Jun. 24 2020), available at https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/06/covid-19-spreads-in-womens-prison-where-sexual-abuse-prompted-federal-probe-say-inmates-and-advocates. As of June 2020, two prisoners had died from complications brought about by COVID-19, and 114 inmates and 77 staff had confirmed cases of the virus.{11} 11 Id.; see also COVID-19 Outbreak Hits North Carolina Women’s Prison, AP (Jul. 6, 2020), available at https://apnews.com/d31753bdb3dac1680bffb24a067cd9aa. On July 6, authorities announced that 45 inmates tested positive for COVID-19 over the past weekend at the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women in Raleigh.{12} 12 https://apnews.com/d31753bdb3dac1680bffb24a067cd9aa. In May, the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women had 165 COVID-19 positive prisoners, the most of any facility in that state. Two women died, and nearly every prisoner in one dormitory had the virus.{13} 13 https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/05/14/what-women-dying-in-prison-from-covid-19-tell-us-about-female-incarceration. As of July 29, Florida reported nearly 1,000 COVID-19 cases and three deaths at three female facilities in Marion.{14} 14 https://www.clickorlando.com/news/local/2020/07/29/three-inmates-in-state-prisons-in-marion-county-die-of-covid-19.

At the federal level, women fare no better. At a medical prison center in Fort Worth, Texas, the COVID-19 virus appears to be raging throughout the facility unchecked, with more than 500 women testing positive for the virus in one of the largest confirmed outbreaks at a federal prison.{15} 15 Over 500 Inmates Test Positive for Coronavirus at Texas Federal Medical Prison, TIME (Jul 21, 2020), available at https://time.com/5869865/texas-coronavirus-federal-prison-fmc-carswell. At Federal Medical Center Carswell, a federal prison in Fort Worth, women sleep four to a room and the rooms have no doors. As COVID-19 tore through the Texas prison — cases grew from 50 on July 7 to 571 by July 23 — staff shut off the air conditioning and hung plastic curtains in the doorways to stop the virus’ spread.{16} 16 https://theappeal.org/coronavirus-in-jails-and-prisons-35. Carswell made news early in the pandemic after the death of Andrea Circle Bear. The 30-year-old was eight and a half months into a high-risk pregnancy when she was transferred from a South Dakota jail to FMC Carswell. She became ill shortly after her arrival, was hospitalized, and was placed on a ventilator the same day her baby was delivered via cesarean section. She died four weeks later.{17} 17 Id. On July 10, there were over 90 active cases at Carswell.{18} 18 Id. On July 12, 69-year-old Sandra Kincaid became the second woman to die at Carswell from the virus. The third, 51-year-old Teresa Ely, died on July 20.{19} 19 https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-510-women-positive-reality-winner-texas-medical-prison/.

The pandemic has amplified all of the deficiencies in state and federal jails and prisons across the country, especially for the less visible, overlooked women behind bars, so many of whom have underlying medical conditions exacerbated by mental health conditions and years of poor health care.

A Different Attack on Women: The Criminalization of Abortion and Pregnancy

Since the 2016 presidential election and subsequent federal judicial appointments, at least 30 states across the nation have introduced some form of abortion ban in their respective legislatures.{20} 20 What’s Going on in the Fight Over US Abortion Rights?, BBC News (Jun. 14, 2019), available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-47940659. Many, if not all, of these states have passed some form of what has become known as “heartbeat bills,” which attempt to redefine a fetus as a human being and proscribe abortions as soon as a fetal heartbeat is detectable — which can occur as early as six weeks after conception, earlier than most women first realize they are pregnant.{21} 21 Reasons a Woman May Not Know She’s Pregnant at Six Weeks, CNN (May 9, 2020), available at https://www.cnn.com/2019/05/09/health/pregnancy-at-six-weeks/index.html. The majority of states being studied by the Women in Criminal Defense Subcommittee on Abortion Laws for a report on expanded criminal liability in a post-Roe world have enacted so-called “triggering” statutes that will ban nearly all abortions if Roe v. Wade is overturned. Every one of these states has existing criminal laws on the books that would inevitably expand the scope of abortion laws, leading to greater and more expansive criminal liability not only for the women having abortions, but also for anyone who helps them along the way. What is also clear is that prosecutors will increasingly rely on anti-abortion laws to support and justify an interpretation of child abuse, drug delivery or other laws as giving them the authority to arrest pregnant women for posing risks or causing harm to their “unborn children.”

Examples of this expanded liability can be found in Arkansas’ and Kentucky’s anti-abortion legislation. Both states have enacted “triggering” statues that criminalize abortion in the event of Roe’s reversal. Indeed, Arkansas has decried Roe v. Wade as a “crime against humanity.”{22} 22 Ark. Code Ann. § 5-61-302; Ark. Code Ann. § 5-61-304(a); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 311.772. Moreover, each state has passed its own version of the “heartbeat bill,” and has taken steps to redefine the meaning of the word “person” to include a fertilized human egg.{23} 23 Ark. Code Ann. § 5-1-102; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 311.720. Interestingly, both states have given the would-be mother criminal immunity if she violates the abortion ban but have criminal statutes imposing broad-based, third-party liability that would extend criminal liability to those who “aid and abet” a woman in her attempt to seek an abortion. Among them, Arkansas has codified its common law accomplice liability, which provides that a person is an accomplice of another person in the commission of that offense if, acting with respect to that particular result with the kind of culpable mental state sufficient for the commission of the offense, the person: (1) solicits, advises, encourages, or coerces the other person to engage in the conduct causing the particular result; or (2) aids, agrees to aid, or attempts to aid the other person in planning or engaging in the conduct causing the particular result. …”{24} 24 Ark. Code § 5-2-403.

The new anti-abortion laws and the possibility that Roe will be overturned open the door to mass criminalization on an unprecedented scale. Though almost all these new statutes have been challenged in federal court, if they survive their current constitutional challenges, even in part, the potential consequences for the criminal justice system will be staggering.

At least 38 states and the federal government have so-called fetal homicide laws, which treat the fetus as a potential crime victim separate and apart from the woman who carries it. The effect of such a change will necessarily result in vastly expanded criminal liability for women.

Horror stories already abound. In 2015, law enforcement authorities in Arkansas believed a woman named Anne Bynum had taken steps to obtain an abortion. After a stillbirth, Ms. Bynum safeguarded the fetal remains and, several hours later, brought those remains to a hospital, asking to see a doctor. Ms. Bynum was arrested five days later on two felony charges: “concealing a birth” (carrying a potential six-year prison sentence and $10,000 fine) and “abuse of a corpse” (carrying a sentence of up to 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine.) Ms. Bynum was convicted of “concealing a birth.” The prosecutor argued that the jury should convict Ms. Bynum because she had not told her mother she was pregnant and because she had temporarily placed the stillborn fetus in her car before going to the hospital. He made this claim despite evidence that she told many people about her pregnancy, contacted several people after the stillbirth, and then went to the hospital with the fetal remains. The jury nevertheless convicted Ms. Bynum and sentenced her to six years in prison. Although Ms. Bynum’s conviction was overturned, the Arkansas Court of Appeals sent the case back to the trial court, which allowed the prosecutor to retry Ms. Bynum on the same charge. The case was finally resolved with a plea to a “non-criminal” violation.

Meanwhile, several hundred women in the United States have already been prosecuted by zealous prosecutors for the crimes of fetal assault, depraved heart murder, delivery of a controlled substance, chemical endangerment of a fetus, manslaughter, feticide, child abuse, reckless injury to a child, concealing a birth, concealing a death, abuse of a corpse, neglect of a minor, attempted procurement of a miscarriage, and reckless homicide — for their pregnancy-related outcomes.{25} 25 Lynn M. Paltrow & Jeanne Flavin, Arrests of and Forced Interventions on Pregnant Women in the United States, 1973–2005: Implications for Women’s Legal Status and Public Health, 38 J. Health Pol. Pol’y & L. 299, 334 (2013); Wendy A. Bach, Prosecuting Poverty, Criminalizing Care, 60 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 809, 842 n.213 (2019); Editorial, A Woman’s Rights, N.Y. Times (2018); https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/12/28/opinion/pregnancy-women-pro-life-abortion.html; Khiara M. Bridges, Race, Pregnancy, and Opioid Epidemic: White Privilege and the Criminalization of Opioid Use During Pregnancy, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 770 (2020). While legal challenges work their way through the court system, thousands of women — and men — will suffer serious criminal convictions that will destroy their futures and those of their families, for decades to come.

The NACDL I have had the great honor of leading for the last year is the bright spot on the horizon. I end my year as president knowing that NACDL is resolute in its commitment to combat over-criminalization and mass incarceration, and redress implicit sexism, racism and bias in the criminal justice system. We still have much to do.

About the Author

Nina J. Ginsberg, a founding partner at DiMuroGinsberg, P.C., in Alexandria, Virginia, has practiced criminal law for more than 35 years. She has represented individuals and corporations in a wide range of matters, with a focus on national security law, white collar investigations and prosecution, financial and securities fraud, computer crime, copyright fraud, and professional ethics.

Nina J. Ginsberg (NACDL Member)

DiMuroGinsberg, P.C.

Alexandria, Virginia

703-684-4333

nginsberg@dimuro.com

www.dimuro.com

@DiMuroGinsberg